Will the visibility of environmental damage in Ukraine translate into action to address the risks it poses to human health and ecosystems?

An unprecedented volume of environmental data is being gathered on the invasion of Ukraine. In this post, Doug Weir explores what kind of data is being gathered, and by whom, as well as the environmental narratives that are developing and the implications of this level of documentation.

A comparative deluge of data

The environmental dimensions of all armed conflicts are becoming ever more visible. There are a number of reasons for this: improved access to earth observation data; new monitoring methodologies; more organisations and individuals actively collecting data; communication pathways becoming more immediate; and all amid growing societal interest in environmental protection.

Should the current level of attention be sustained, the invasion of Ukraine may well prove to be the most highly observed conflict in history. The sheer volume of data, be it from satellite imagery, social or traditional media, is overwhelming. Both within and alongside this deluge is environmental data, and data that provides clues to the environmental conditions in affected areas.

This post examines the conflict’s data collection landscape, and the potential implications of this dynamic but before doing so it is worth revisiting the what, why and how of environmental data collection in conflicts.

Collecting data on the environmental dimensions of conflicts

Conflicts cause and contribute to a wide range of environmental problems. This is particularly true when the fighting is prolonged, intense and affects a large geographical area. And, as is also the case in Ukraine, when war impacts urban, industrial, agricultural and terrestrial and marine natural areas. There are many ways to characterise the damage. It may be direct or indirect, transient or permanent, widespread or localised, cumulative or unique, deliberate or incidental.

Typically, several of these characteristics apply simultaneously. For example, where weeks of Russian bombardment of a steelworks with a diverse range of weapons remobilises existing pollution linked to the site’s former use, and disperses heavy metals and energetic compounds from the munitions. Or where Ukraine targets a former coal mine to destroy a Russian ammunition stockpile concealed there, creating a similar outcome.

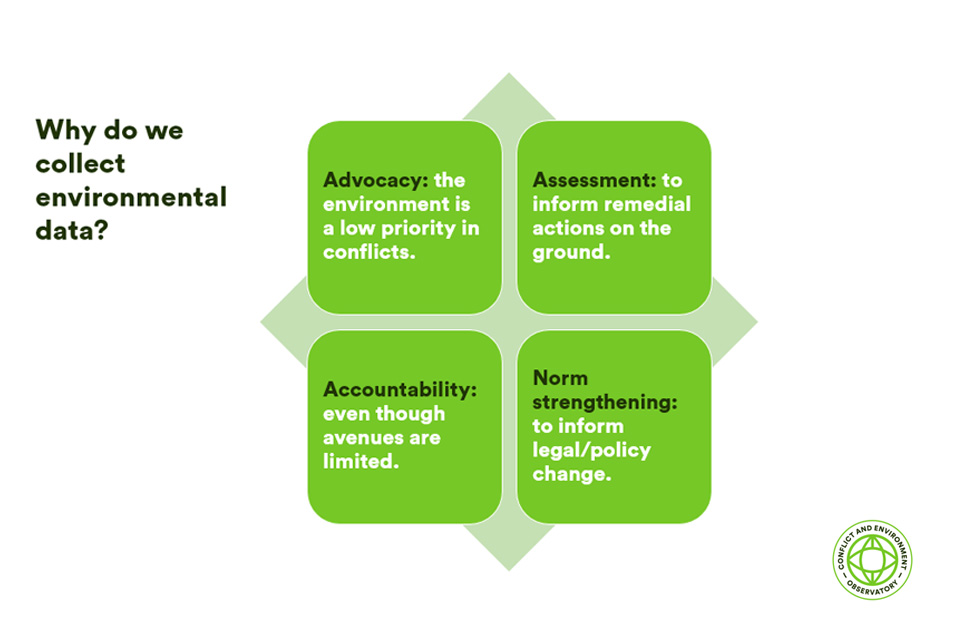

But why is it important to document and publicise these incidents, particularly in the face of so much human suffering? Both human rights and ecosystems depend on a healthy environment, irrespective of the hopefully temporary conditions created by conflict. However, the environment is typically under-prioritised during conflicts. Addressing this requires advocacy, indeed awareness-raising is the foundation upon which much else depends. This includes creating the political or financial conditions for assistance and technical assessments on the ground, and for subsequent remedial measures to reduce harm. Advocacy can promote accountability, whether for financial reparations or criminal prosecutions. It is also vital for the norm development that can help reduce future harms. In the case of Ukraine, one such legacy may be the way the conflict has foregrounded the necessity of strengthening protection for nuclear sites during conflict and occupation.

However, conflicts create considerable barriers for environmental data collection. Chief among these is the loss of access to affected areas, and the disruption of peacetime monitoring, whether automated or simply through the day to day activities of the state, academics or civil society. Even though environmental protection tends to be viewed politically as a low priority, at times the fate of the environment, or components of it, can become acutely politicised, or data about it subject to manipulation, distorted into disinformation or even weaponised.

Remote monitoring as a solution

Overcoming the barriers that conflicts create for environmental data collection has encouraged the growth of remote monitoring. This has been facilitated by increased access to satellite imagery, and the widespread use of social media channels, such as Telegram, in Ukraine’s case. When combined with a range of sources, be it grey literature, traditional media reporting or local knowledge and, often, the wisdom of the crowd, it becomes possible to begin to remotely map the contours of environmental harm.

However, assessments based solely on remote monitoring have limitations. The precise characterisation of health or ecological risks still requires dedicated studies or sampling on the ground. Similarly, the window that remote monitoring provides can just be a snapshot of wider temporal or geographic trends, or may not aid understanding of the role of pre-existing issues at a given site, nor allow the observer to fully understand complex environmental relationships.

The observer must also be mindful of bias, some environmental incidents are just more visible than others, whether you are at ground level or in orbit. Fires, oil spills and deforestation can be easy to track, their health or ecological consequences far less so; causal relationships are often complex. And as noted, sources must be closely scrutinised, environmental issues are not immune from being manipulated for propaganda or disinformation purposes. Equally, there are often imbalances in who is reporting, be it on social or traditional media, and this can easily distort the relative coverage of particular issues, or how they are framed.

Data challenges in Ukraine

The initial pace, intensity and geographic scope of the invasion posed a huge challenge to all individuals and institutions tracking the invasion’s consequences, be they environmental or humanitarian. In this it’s not simply a question of the data that you can gather, but how that data is stored and verified, and for what purpose.

New databases were created, or existing systems repurposed; we scrambled to rekindle or make new connections with local experts. Many of those Ukrainian environmental experts found themselves displaced, and the invasion rapidly disrupted automated monitoring systems, be they on air quality or radiation. Cloud cover proved a persistent problem, particularly between February and May, and government calls to restrict sharing of the locations of images and videos impacted the identification and verification of incidents. With future legal cases a very real prospect, and with social media posts notoriously ephemeral, we partnered with Mnemonic, an NGO with a detailed social media archiving system, to ensure important data was not lost.

As was expected, many of the most visible incidents have received the most attention, but we have also seen how popular narratives displaced attention on the environment. For example, the siege of the Azovstal steelworks focused on the forces fighting to hold it, and the civilians sheltering below it. The environmental implications of the siege were scarcely mentioned.1 Meanwhile, the struggle for control of Snake Island became one of resistance and national pride with no room for consideration of the impact on the island’s ecology, or that of the marine protected area that surrounds it.

Data opportunities in Ukraine

In spite of these challenges, the environmental dimensions of the invasion are comparatively well documented thanks to a confluence of factors. The invasion has built on a pre-existing environmental narrative that developed in response to the conditions and concerns documented in the Donbas region and Crimea. This narrative drew attention to the risks of environmental emergencies linked to damage or disruption to industrial facilities and remains highly relevant, with nuclear facilities now added to the list of sites of concern.

Since February, further environmental narratives have been developed and amplified by the Ukrainian authorities, both domestically and through international environmental diplomacy. This has included weekly publications on incidents which, in an unprecedented move, have also been circulated to national delegations to the UNEP in Nairobi. Ukraine’s network of environmental organisations, researchers and experts have also greatly contributed to data collection and dissemination, adding important contextual information based on their situated knowledge.

However, as the conflict has gone on, we have seen a divergence in this narrative. Between February and early April, all parties focused on the immediate damage and shock. For the Ukrainian authorities, this has subsequently been subsumed into an almost singular focus on the financial cost of damage, and on the question of reparations. At the behest of Ukraine’s parliament, experts were gathered to urgently develop damage valuation methodologies; a process that may be of limited utility in the medium to long-term: should a future reparations mechanism be found, it will decide on how different components of the environment can be valued. Far better, many advised, to focus on gathering and preserving the data itself.

Ukrainian civil society experts have become increasingly vocal in their criticism of this approach, the financial cost of harm alone can tell you precious little about the true consequences for ecosystems, species or for health. Ukrainian NGOs have also been vocal in their scrutiny of emergency laws that could prove environmentally damaging, and of plans for post-conflict reconstruction and recovery. They argue that the war should be a turning point that facilitates Ukraine’s transition away from its industrial past, leaving it with stronger environmental governance and more sustainable development.

The data collection ecosystem

Those Ukrainian NGOs, like Ecoaction, are now part of a wider data collection ecosystem for the conflict. This also includes organisations like Environment People Law, that have been documenting harm in the Donbas for many years, the biodiversity-focused Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group, which has reoriented to the consequences of the conflict, and new arrivals formed by experts from Ukraine and neighbouring countries such as the Ukraine War Environmental Consequences Work Group.

In many cases, these organisations can call on local domestic expertise, with experts also contributing to the Ministry of the Environmental Protection and Natural Resources efforts to track and value damage. This has included innovative approaches to incident reporting, including an app and a dedicated Telegram channel. Staff of the Ministry’s State Inspectorate of the Environment have been collecting and storing samples from sites attacked by Russia.

In addition to these domestic initiatives are those by international NGOs with a focus on the environment or humanitarian issues, such as Zoï Environment Network, PAX, the REACH initiative and ourselves, to name just four, as well as academic institutions around the world. All are taking different but potentially complementary approaches. For example, our incident database focuses on depth and risk assessment, and is primarily supported by social media reporting and remote sensing. We are collaborating closely with Zoï Environment Network, whose Ecodozor platform is primarily fed by governmental information and local and national traditional media reporting, thus providing breadth.

The data we collect supports our media work, and feeds into our communication products, which includes a joint series of thematic briefings, or presentations at events such as that below.

International organisations like UNEP and OCHA have deployed specialised staff and, in UNEP’s case are trialling the integration of data collection by NGOs, including ourselves, Zoï and PAX as part of its efforts to monitor the environmental situation. Others like the OSCE have longstanding environmental activities in the country, which it intends to sustain despite current political challenges.

This characterisation of the increasingly diverse data collection ecosystem is far from exhaustive.

Data collection priorities in Ukraine

Compared with many countries affected by armed conflicts, Ukraine has a relative abundance of environmental data, and actors gathering it. Six months into the invasion is perhaps a good time to reflect on how data coverage could be made more comprehensive. For example, through creative ways to connect remotely gathered data with locally collected information. This would require closer cooperation between international and local expertise, and experimentation with methodologies such as “civilian science”. There is also the question of data coordination. It seems likely that an independent but centralised repository with a publicly accessible online portal could greatly benefit advocacy, analysis, response and recovery, and help avoid duplication. However, this would need to be adequately resourced, and thought would be needed on its outputs, if it were to avoid becoming a big data graveyard.

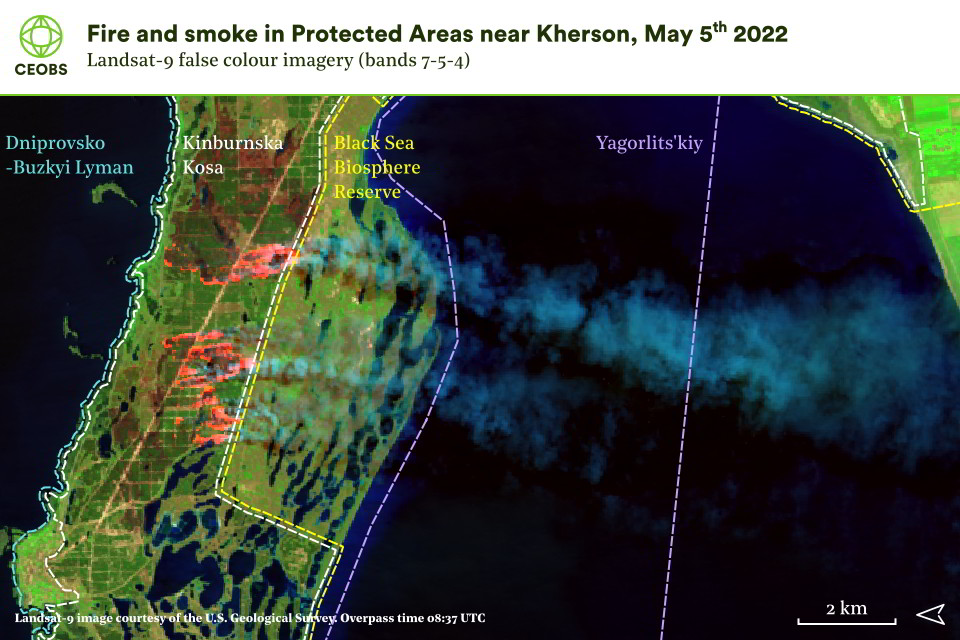

Work should begin on analysing longer-term changes and trends, for example concerning biodiversity and damage to Protected Areas. The same goes for indirect environmental impacts, where causal relationships may require a greater degree of analysis to understand, as well as any new changes to sites where damage has been reported, for example where initial containment or other remedial actions have taken place. It would also be wise to scrutinise what is happening to potentially damaged sites in occupied areas, given what we know from the past governance of areas of the Donbas outside Ukrainian control.

Another important task is to revisit the why of data collection, and how it will be used. Is the focus chiefly political? Is it on the future prospect of compensation? Is it to inform the protection of civilians or ecosystems, or to inform assessment or remediation? Interrogating the why and how help ensure that we get the basics of data collection, verification and storage right.

As the war goes on, and alongside the direct and indirect damage being caused by the physical effects of the fighting, it will be increasingly important to monitor changes in domestic environmental governance that may have implications for the environment. It is a constant of conflicts that governance suffers, and in many cases, this can create a “tail” of environmental harm that can be national in scope and continue for years.

Looking ahead

Since February, media interest in the environmental consequences of the invasion has been unprecedented. Just as unprecedented is the number and range of organisations that are collecting environmental data.

But what, if anything, will that increased visibility translate into? Will it, as is hoped by the Ukrainian authorities, eventually contribute to the launch of a UN General Assembly mandated claims commission? Will it, as is hoped by many Ukrainian NGOs, help ensure that the resources are made available for a sustainable recovery? Will it help ensure that donors contribute to a post-conflict environmental assessment and urgent remedial measures? Will it mean that environmental risks are addressed? One study on the Donbas region, with its numerous industrial hazards, found that a strong narrative and visibility did not readily translate into actions on the ground to mitigate those hazards.

Or will the high degree of attention simply contribute to environmental fatigue? Catastrophic single incidents may not happen, they rarely do. Instead wartime environmental degradation takes place across thousands of incidents across hundreds of square kilometres. This is a tougher sell for the media and the public and, when combined with the drift of attention away from Ukraine as the war grinds on, will make advocacy increasingly difficult.

This perhaps points to another priority for all those working to document the environmental dimensions of the conflict. We will need to find and communicate new and relevant stories to keep the environment on the national and international agendas, indeed doing so will be vital for Ukraine’s sustainable recovery. This can be challenging when the media sometimes demand soundbites or sensationalism but is another reason why we need to study, untangle and articulate the environmental stories that go beyond the immediately obvious.

Doug Weir is CEOBS’ Research and Policy Director, this post is based on a recent presentation for the conference on “The impact of hostilities on Ukraine’s environment and human rights – a civilizational challenge for humankind” in Lviv. Thanks to Eoghan Darbyshire for the graphics and Nickolai Denisov for the feedback.