UK sea-dumped munitions policies mean that it’s a problem that remains both out of sight, and out of mind.

This week’s UN Oceans Conference aims to mobilise action to protect our seas. Sea dumped munitions are a threat to the marine environment globally, and a threat that climate change may exacerbate. In this post, Rowan Smith and Linsey Cottrell explore the risk they pose in British waters, and find that UK policy is falling behind that of Europe.

Introduction

Sea-dumped munitions are a global problem; this includes huge volumes currently lying on the UK’s seabed. After both the first and second world wars obsolete, excess, damaged or seized munitions were dumped at sea. Thousands of tonnes of conventional and chemical weapons remain on the seafloor, where they threaten marine ecosystems, human health and interfere with energy infrastructure development.

For many years, the sea was used for the disposal of a wide range of hazardous industrial and radioactive wastes. Historic dumping of munitions, encouraged by an ‘out of sight, out of mind’ mentality, largely preceding marine protection laws. The 1972 London Convention prohibited the deliberate sea-dumping of munitions – and other waste, but does not require remedial actions for areas contaminated by earlier disposal activities.

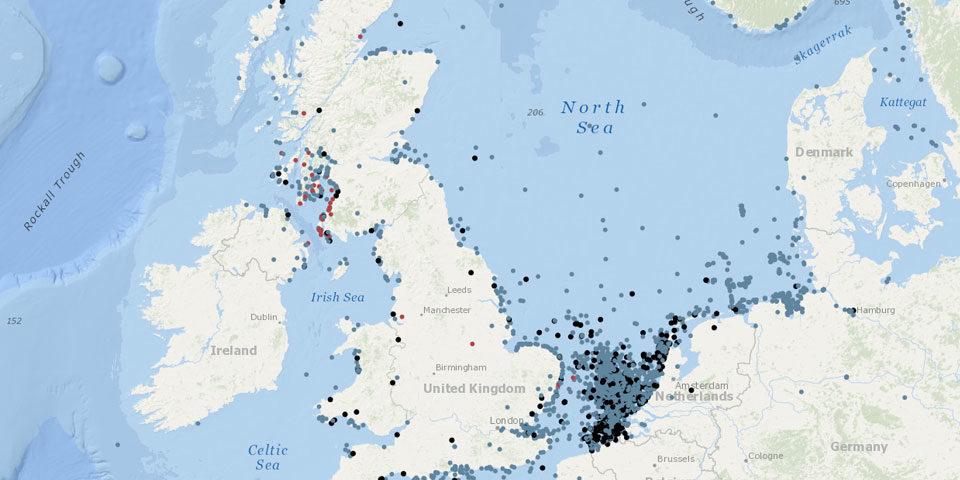

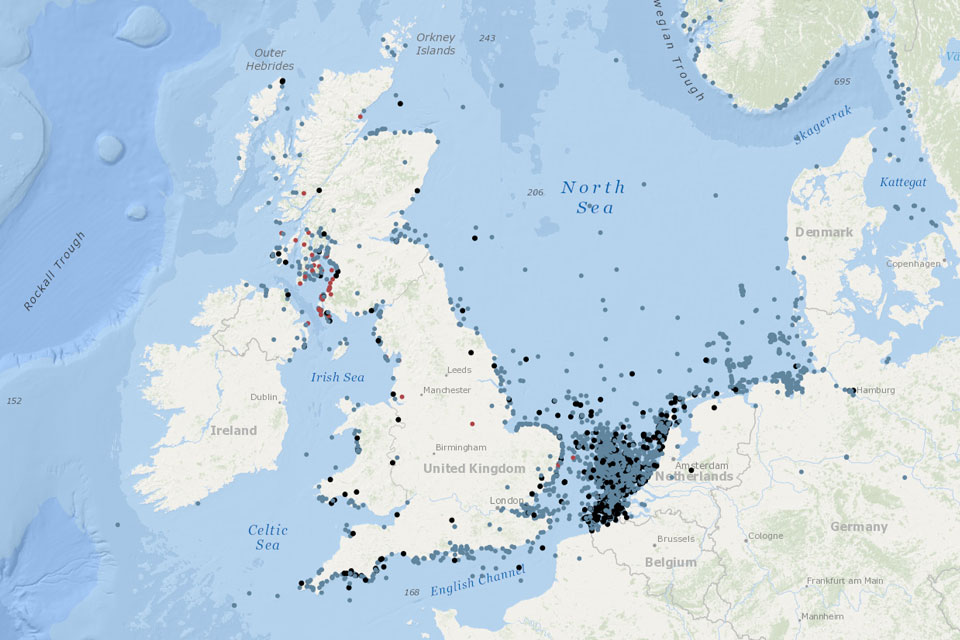

Records are incomplete, but at least 1.2 million tonnes of chemical and conventional munitions were dumped in UK waters. Encounters with chemical, conventional or ‘unknown’ munitions in UK waters between 1999 and 2017, and which were reported to OSPAR (the body established by the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic), are shown below. Annual incidents peaked in 2003, perhaps due to increased fishing and seabed activity. The Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission (HELCOM) also collects incident data; its data shows incidents peaking in the early 1990s.

Although historic dumping sites were recorded at the time, the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) has admitted to losing or accidentally destroying documents containing munition locations, volumes and types. Evidence also suggests that a large percentage of documented munitions destined for pre-designated sites never made it there. Instead they were jettisoned on route, making any records that do remain inaccurate.

Such is the case for Beaufort’s Dyke, a natural ocean depression in the Irish Sea, and which was used as the UK’s primary munition dumping ground. Beaufort’s Dyke has a maximum depth of around 300 metres, and its depth is largely believed to have minimised the associated environmental risks. Nevertheless, incomplete data and a lack of accurate records mean that the distribution of munitions in Beaufort’s Dyke, and UK in territorial waters more broadly, is unclear. Their presence poses ongoing risks to shipping, fishing, aquaculture, offshore marine and energy infrastructure and other blue economy sectors.

Munitions and the marine environment

Research into the consequences for marine organisms had been relatively neglected until recently. Similarly, the potential risks to the human food chain are not fully understood.

Understanding these risks is complicated because the behaviour of sea-dumped munitions varies. Factors include the munition type, whether chemical agents or explosives, the environmental conditions on the seafloor, and the corrosion rate of their casings. As the level of corrosion increases over time, there is an increased risk that harmful munition constituents will leak, impacting the marine environment or entering the marine food chain. Since environmental conditions like salinity, turbulence, pH, dissolved oxygen content and temperature vary widely by location, the rate and impact from leaks is difficult to predict and assess.

Recent monitoring and research

Studies and advances in monitoring techniques have identified localised chemical concentrations, with the potential to adversely impact marine organisms. Much of this research has been focused in the Baltic Sea and North Sea, where there are an estimated 1.6 million tonnes of dumped conventional and chemical munitions in German territorial waters alone. Commercial fish species – such as Baltic cod – have been found to contain trace concentrations of phenylarsenic – a chemical weapons agent – in muscle tissue: detectable concentrations were found in around 14% of sampled fish.

This and similar studies indicate the potential risk to human health from seafood consumption. They also highlight the need for the assessment of future exposure risks, and for the adoption of a precautionary approach in the vicinity of munition-dumping sites until such assessments are completed. Although not yet fully studied, it is predicted that climate change may increase the risks to marine biota from sea-dumped munitions, due to rising sea temperatures, increased seawater acidity and higher frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, including storms. All these factors can accelerate the corrosion rates of casings, and therefore the frequency of leaks.

In Europe, there are calls for a shift towards the active management of dumpsites, with policymakers looking to implement improved management strategies, subject to funding. New strategies include the EU-funded BASTA project, which uses autonomous underwater vehicles with artificial intelligence to automatically detect and identify dumped munitions on the seafloor.

Undertaking detailed surveys and identifying the types and volume of munitions is critical for informing management options. The Decision Aid for Munition Management (DAIMON) project provides guidance and tools designed to support environmental assessment and remediation decisions. NATO’s Open Spirit operation also aims to actively map and clear underwater ordnance in the Baltic Sea.

Current UK strategy

Compared to Europe, there is an absence of UK-focused research and proactive initiatives to deal with legacy munitions. For example, the UK’s Marine Strategy does not specifically refer to sea-dumped munitions. The MoD is responsible for removing or disposing of munitions when their presence affects human health or safety. However, it only does so on an ad hoc basis in response to specific reported munitions.1

A 2005 study that was commissioned and funded by the MoD concluded that munitions on the seabed should remain undisturbed. It also found that there was no evidence to link munitions dumped in Beaufort’s Dyke, to toxicity to marine organisms and to risks in the food chain. This was based on the results of a survey by the Marine Laboratory in 1995.2 However, the 2005 report noted that it was not possible to predict the future state of munition casings and that continued monitoring was required.

The UK has a network of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs), within which intentionally destroying the habitats and species that justified their designation as an MPA is an offence. The UK’s Joint Nature Conservation Committee (JNCC) note that some MPAs may be sensitive to pressures from industrial pollution and waste disposal, including munitions, but that “little is known and this is not assessed due to lack of evidence”. The MoD uses in-situ detonation to deal with explosive ordnance finds. However, this method can lead to significant physical harm to marine mammals, including noise trauma to harbour porpoises and cause the release of toxic chemical contaminants into the environment.

In situ detonation has drawn criticism because it can mean noise levels exceeding 300 decibels, enough to deafen cetaceans and induce strandings.3 The JNCC has an interim position on alternatives to the high-order detonation of explosive ordnance, and guidance is in preparation to minimise environmental impacts. A joint position statement by UK authorities support the development and use of ‘lower noise’ alternatives, and strongly recommends early engagement with nature conservation bodies for all ordnance clearance applications.

The MoD has developed Environmental Protection Guidelines (EPG) in consultation with the JNCC. These prohibit the firing of munitions or detonating unexploded ordnance inside or within 500 yards of a MPA, unless programmed within an established weapons range. The EPG relate to military activities and exercises, but the JNCC note a risk that the EPG may not sufficiently address conservation objectives, for example in the Special Protection Area (SPA) in the Irish Sea. A Freedom of Information request submitted on MoD policy for the management of legacy munitions was deemed ongoing and withheld.4

Future action needed

The UK’s Marine Strategy does not include specific plans to assess or monitor the environmental risks from sea-dumped munitions. In the absence of an active management plan, the current approach focuses on dealing with explosive ordnance risks relating to marine infrastructure and projects, or to isolated incidents. To date, the presumed depth of munitions dumped at and around Beaufort’s Dyke is largely believed to have minimised risks. However, with the increased exploitation of deep-sea fish stocks, the ongoing knowledge gaps, and a greater risk for harmful munition components to leak, there is a need to review sea-dumped munition policies. There are currently three priority areas.

Firstly, in order to supplement the poor existing records, mapping surveys are needed on the spatial distribution of munitions. Secondly, and based on the results of the mapping surveys, the condition of munition casings should be assessed, prioritising high value MPAs and other sensitive areas. This would help characterise the risk posed by munitions now and in the future. Finally, an open access database on sites should be established, supported by guidance specific to UK waters and environmental conditions. Both would support assessment, management and remediation decisions, and parallel the DAIMON Baltic Sea project, and the mapping data provided through the European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet).

While Europe is demonstrating how active and engaged management can be put in place for sea-dumped munitions, the UK is lagging behind when it comes to both transparency, and policies.

Rowan Smith is currently at Strathclyde University, studying a MSc in Sustainability and Environmental Science. Linsey Cottrell is CEOBS’ Environmental Policy Officer. This research was the result of CEOBS supporting Strathclyde University’s independent study in collaboration with industry programme.

- RS personal communication Marine Scotland and R Smith, 2022.

- The 1995 study involved the collection of samples of seabed sediment and commercially exploited fish and shellfish. Samples were analysed for heavy metals (aluminium, arsenic, cadmium, chromium, copper, lead, mercury, nickel and zinc), explosive and propellant residues (nitroglycerine, 2,4,6 trinitrotoluene, RDX and tetryl), chemical weapons agents (phosgene or mustard gas) and elemental phosphorus.

- The Stop Sea Blasts Campaign advocates the adoption of ‘low-order deflagration’, a quieter alternative management technique to the current high-order detonation utilised for sea-dumped munitions, to combat noise trauma in marine mammals. Deflagration causes the explosive contents inside munitions to ‘burn out’ but not detonate.

- FoI request to the UK MoD made by R. Smith, dated 12-1-2022, response received 8-2-2022.