The apparent rejection of transparent accounting shows why it should be the UNFCCC and IPCC setting military emissions reporting standards, and not NATO.

NATO’s self-stated aim is to be a leader on climate change and security but its pledges on emissions cuts at the 2022 Madrid summit will be meaningless without external verification of the methodology used to calculate them.

NATO’s “responsibility to reduce emissions”

At the opening of NATO’s 2022 summit in Madrid, its Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg announced an organisational cut in Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions of at least 45% by 2030, and to net zero by 2050. “We have conducted a thorough analysis of how to do this”, said Stoltenburg. “It will not be easy. But it can be done.” While the announcement, which builds on pledges made at its summit in 2021, made the headlines, it was unclear whether this applied only to NATO’s institutional emissions, or to the emissions of all of NATO members as well.

It is the militaries of its members that are NATO’s primary source of emissions, not NATO as an institution. In spite of Stoltenburg’s climate enthusiasm, there have been few signs of consensus among its members for cuts. Some members, such as the UK and US, have set targets linked to national 2050 net zero goals.

Emissions pledges are to be a matter of faith

However, irrespective of the common target, what is more worrying is that it appears that a methodology that NATO has developed to help both it and its members count their emissions will not be made public. Development of the methodology was announced in 2021, when it became clear that the alliance was unable to pledge emissions cuts because neither it, nor its members, knew what their emissions were. A long-running culture of environmental and climate exceptionalism has left militaries lagging behind many other private and public bodies on emissions tracking.

According to Stoltenburg, the methodology, which covers NATO’s military and civilian emissions “sets out what to count and how to count it, and it will be made available to all Allies to help them reduce their own military emissions.” Adding: “This is vital, because what gets measured, can get cut.” But in spite of expectations, and in a rejection of good practice, there was no pledge to make the methodology public.

The inability to scrutinise or assess how NATO, and those of its members that adopt the methodology, are counting their emissions means that external stakeholders, whether they are policymakers, researchers or civil society will be unable to determine the veracity of any claimed cuts or pledges. In essence, NATO is asking for its emissions reduction policy to be a matter of faith.

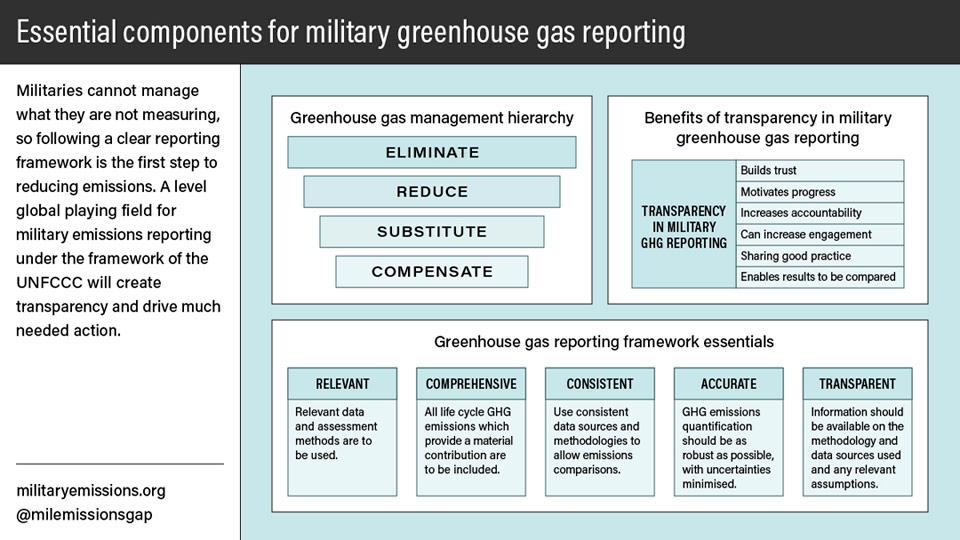

CEOBS recently published a review of which emissions militaries should be counting. The report highlighted the vital role of transparency, not just in building confidence in reporting but also as a source of identifying and sharing best practice, and in driving the institutional change necessary to deal with the huge challenge posed by the massive climate bootprint of militaries.

Former NATO spokesperson Jamie Shea, raised the question of openness in an interview with CNBC: “The NGO community will want this to be a public methodology so that it is not just left for NATO to decide if it is doing well or not, but the community of climate science can also say whether this is a proper methodology and if NATO is really moving in that direction.” As far as we can tell, it would appear that neither the NGO or scientific community will get the chance to asses this.

NATO’s decision sends the wrong message on global military emissions

This apparent rejection of transparency and good practice may well have global implications. Our joint Military Emissions Gap project has already shown that state reporting of military emissions to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is poor. Despite an attempt to position itself as a leader on climate change and security, NATO risks worsening this further by sending a message to other states that military emissions data, and the calculations behind it, should not be made public. Only a handful of the top 60 military spending governments state that they do not report emissions because of national security concerns.

Unless it publishes its methodology, NATO’s disappointing stance lends further weight to the argument that, while some states may prefer that debate on mitigating military emissions takes place within NATO itself, the global climate would be better served by it being addressed by the UNFCCC. Debate on cuts in this universal body, and the development of broader and more comprehensive reporting standards by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, would radically increase confidence in global military emissions mitigation efforts.

Doug Weir is CEOBS’ Research and Policy Director