A lack of transparency makes it hard to calculate the true scale of military emissions but it’s clear they are significant.

Militaries are huge energy users, making a significant contribution to climate change. Military emission reduction targets should be included in national climate strategies but we first need to better understand their emissions. In this blog, Linsey Cottrell and Eoghan Darbyshire explore why they emit so much, what needs to change, and why it’s not just a question of fuel.

Spending up, emissions up

Faced with the climate crisis, and global military expenditure rising to almost US $2 trillion in 2020, there is a critical need for the military to be included in commitments by states to reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Reducing emissions should not be the sole aim. This is because focusing only on transitioning the military to non-fossil fuel technology without addressing the whole life environmental cost of military technology and of military activities, risks overlooking the wider impact of military activities on the environment.

This post specifically examines emissions linked to military activities, this post explores how conflicts themselves influence GHG emissions.

Fuel, equipment and the supply chain

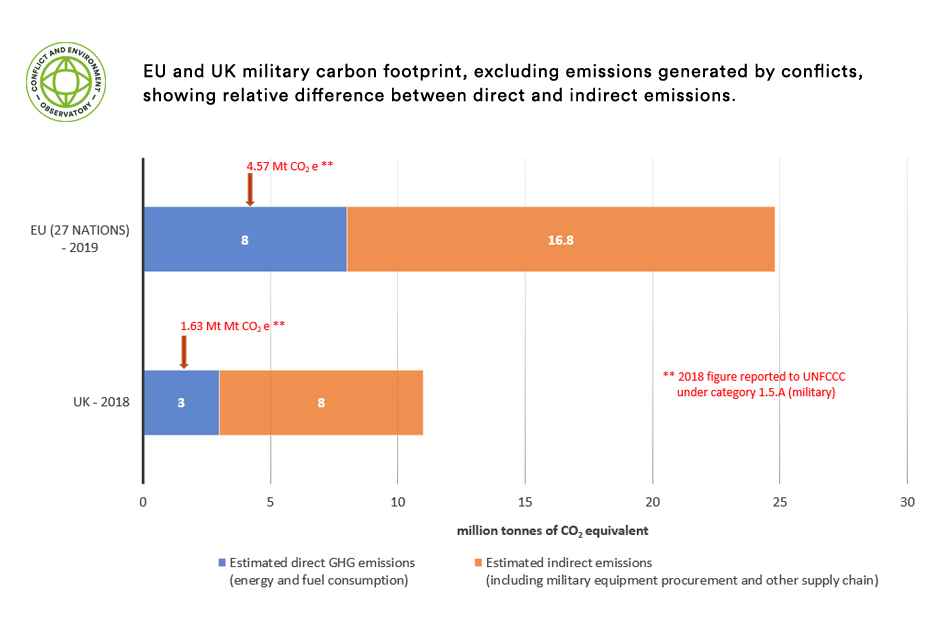

Energy use at military bases and fuel use from the operation of military equipment – such as aircraft, naval vessels and land vehicles – are often seen as the main contributors to military GHG emissions. When the military do report on their emissions, it is this data which is usually provided. However, research into the UK and EU militaries shows that it is military equipment procurement and other supply chains that account for the majority of military emissions. This excludes those related to the impact of conflict operations.1

Figure 1. For 2019, the carbon footprint of the EU military was estimated to be around 24.8 million tCO2e (tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent).This compares with the carbon footprint of the UK military estimated at 11 million tCO2e for 2018. Figures reported by states to the UNFCCC for their militaries are much lower.

Arms production and the military supply chain therefore plays a significant role in the carbon cost of war. In 2019, sales by the largest 25 arms producing companies reached an estimated US $361 billion, an increase of 8.5% compared to 2018. Each sale has its individual carbon cost, from the extraction of raw materials, through to production by arms companies, the use by militaries, decommissioning and end-of-life disposal.

The notion of greener or socially responsible arms production will seem ironic to many. Several military technology companies do however produce Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reports and provide GHG emissions and environmental data. The quality and scope of these CSR reports varies considerably. For example, Lockheed Martin includes the ‘use of sold products’ within its emissions data, whilst the data from many other military technology companies is far less complete. Just as with the gaps in military reporting by governments, there are huge disparities in reporting across the military technology sector.

| Military sector GHG emissions reporting | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Company | Country base | Arms Sales in 2018 | Company wide | Reporting scope | |||

| US $ bn | % of total sales | M tonnes of CO2e (year) | Scope 1 | Scope 2 | Scope 3 | ||

| Lockheed Martin Corp. | United States | 47.2 | 88 | 33.0*(2020) | • | • | ◦ |

| Boeing | United States | 29.1 | 29 | 2.5 (2019) | • | • | ◦ |

| Northrop Grumman Corp. | United States | 26.2 | 87 | 0.4 (2020) | • | • | |

| Raytheon | United States | 23.4 | 87 | 12.7 (2019) | • | • | ◦ |

| General Dynamics Corp. | United States | 22 | 61 | 0.7 (2019) | • | • | |

| BAE Systems | United Kingdom | 21.2 | 95 | 0.5 (2020) | • | • | ◦ |

| Airbus Group | Trans-European | 11.7 | 15 | 444.2*(2020) | • | • | ◦ |

| Leonardo | Italy | 9.8 | 68 | 0.8 (2020) | • | • | ◦ |

| Almaz-Antey | Russia | 9.6 | 98 | Not found | n/a | ||

Figure 2. Table showing arms sales in 2018 (based on the SIPRI database) for the largest military companies and published corporate carbon reporting (where available). • denotes included, ◦ denotes included in part. *Scope 3 includes ‘use of sold products’.

For the EU, large public-interest companies are legally required to provide non-financial reporting, which includes information on their GHG emissions. However, the current guidelines on reporting climate-related information are non-binding. It is hoped that planned amendments will strengthen the EU’s non-financial reporting requirements. Global variability means there are big gaps in the data available and only broad assumptions can be made when estimating climate and other impacts, while closer scrutiny of the publicly available data is also needed.

Aviation and the naval fleet

Contemporary warfare is dominated by aviation. This emits vast quantities of GHGs during production and operation – in 2017 alone the US Air Force purchased US $4.9 billion of fuel. A single mission of two fuel thirsty B-2B bombers in January 2017, flying from the US to Libya, emitted about 1,000 tCO2e. Military jets typically fly at higher altitudes than commercial airlines. As well as emitting greenhouse gases, aircraft flying at high altitude can also cause additional atmospheric heating effects due to the contrails left by aircraft, which can persist as large, thin sheets of cirrus clouds. Contrail cirrus, as well as other non-CO2 effects like NOx emissions from aviation, are significant contributors to the climate warming impacts of aircraft emissions. This means that fuel consumption data alone is not reliable for assessing the full climate impact of military aviation.

As of 2021 the global military aircraft fleet is 53,563, which is more than double the projected civilian fleet of 23,715.2 Overall, aviation represents around 3.5% of climate warming, and the role of military aviation is currently estimated at between 8% to 15% of this total. The contribution from military aircraft is difficult to estimate and likely accounts for the single largest source of uncertainty in global aviation – the primary difficulty arises from the nondisclosure of data on military aviation activity, which underlines the importance of transparent reporting.

Because of the use of more polluting ‘bunker’ fuel, the marine sector is responsible for 2.5% of global GHG emissions and rising. Naval spending is also increasing but again, there is a paucity of data which makes it difficult to estimate global GHG emissions from the naval fleet. Naval ships, together with other military equipment, typically have longer life expectancy than civilian equipment, which risks ‘locking in’ carbon-intense technology and delaying decarbonisation – the new HMS Queen Elizabeth aircraft carrier has an estimated 50-year lifespan.

The merchant fleet tonnage is estimated by UNCTAD to be 2,100 million tonnes, whilst the all-country naval tonnage is around 8.7 million tonnes. These figures suggest that the naval fleet accounts for just 0.42% of total tonnage, but as civilian shipping begins to address its GHG emissions, the military may be left well behind. The lack of baseline data for the military will also make any promised progress difficult to track. As the New Zealand navy concede, for the next few decades fleets will continue to rely on diesel fuel – during which time more operations are expected as a direct result of responding to climate change threats or emergencies.

Biofuel has been touted as an alternative to fossil fuels for the military, but the environmental sustainability of biofuels has been questioned and their use may remain just-over-the-horizon for a long time. As such, militaries proposing to use biofuels or other synthetic fuels (such as ammonia), or even mobile nuclear reactors, will need to be cognisant of their indirect emissions and other environmental costs.

Military estates

Military training lands and estates are estimated to cover between 1-6% of the global land surface. Because of this, how they are used and managed could have a significant bearing on global GHG emissions. The military training estate often includes areas of ecological importance, and is typically closed to the public and remains relatively undisturbed, compared with other intense land uses. Improved land management to optimise carbon sequestration and minimise carbon losses from soil is needed. These improvements could also increase biodiversity and help build climate resilience.

Soil temperature, drainage, erosion and deposition can all influence carbon sequestration and losses, meaning that improved land management and reduced soil disturbance can increase soil’s carbon content. Military lands have significant but underutilised scope for carbon sequestration – despite a scoping study in 1995 showing the potential, the US Department of Defense (DoD) has not developed the idea until recently. It is also now flagged as one of the key actions by its Climate21 expert panel. Nevertheless, we are a long way from policy coherence over land management, as the backdrop of tropical forest clearance plans in Guam due to the DoD’s planned military base extensions demonstrate.

Where the remediation of contaminated land relating to the military estate is needed, sustainable remediation practices must also be followed, ensuring the protection of people and the wider environment from unacceptable risks, and balancing this with sustainability objectives such as minimising GHG emissions.

Wildfires can be significant sources of emissions and reduce the ability of vegetation and soils to store carbon. Recent incidents of landscape fires on military lands – such as those in Scotland, Wales, Kenya, Alaska and Australia – also highlight the need for better land use practices and improved emergency response, where there is increased fire risks. Unless climate change adaptation measures are in place, higher summer temperatures and drought conditions will increase fire risks, for example during live firing exercises.

An academic study in Israel noted the high prevalence of fire scars near training grounds. While in 2018, a fire triggered by military rocket testing in Germany caused widespread damage to moorland, with smoke reported more than 100 km away. In cases where fires occur on military training land, tackling the blaze can be complex and dangerous due to the presence of unexploded ordnance. Planned burn operations are also in practice to reduce the risk of wildfires on military land.

Military training exercises themselves of course also generate significant GHG emissions, including from land degradation. This is particularly true when undertaken in fragile environments such as semi-arid deserts. We are not aware of assessments in the public domain that examine the carbon footprint of specific training exercises. However, there have been recent pushbacks against training drills due to climate and environmental concerns. Whilst exercises themselves are now incorporating climate security, there must be a commitment to undertake climate and environmental assessments for all military exercises and to mitigate any adverse impacts.

Waste management

Waste management represents approximately 3% of global GHG emissions and the military must both significantly reduce the volume of waste it generates and manage any waste it does produce responsibly. This includes any surplus materiel or equipment, like munitions which are commonly destroyed by open detonation or burning. This can cause ground contamination, generate noxious air pollutants and release greenhouse gases.

Waste disposal practices across the military have been poorly managed in the past, with the use of open burn pits, burial and weak compliance with standard waste management protocols. Poorly regulated commercial operators contracted by the US government to manage waste from military bases in Iraq and Afghanistan, led to inadequate environmental safeguards, improper disposal of waste and poor environmental outcomes. The assessment of the long-term health impacts on US veterans is ongoing. US DoD guidance now prohibits their use unless ‘no feasible alternative exists’. As of March 2019 burns pits were still in operation at several US sites in the Middle East and Afghanistan. The use of waste disposal by open burning has not been eradicated across all militaries.

Military reduction targets and reporting

The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, obliges signatories to publish annual GHG emissions data, but military emissions reporting is voluntary and often not included. We have found that even when it is reported, military GHG emission data is often incomplete. There needs to be far greater transparency and more robust reporting so that emissions can be managed and reduced. It’s a recurring problem, for example the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs’ military expenditure reporting forms do not include fuel costs, and International Energy Agency statistics also exclude military energy use.

NATO has now published its Climate Change and Security Action Plan, which outlines the development of a methodology to measure GHG emissions and which ‘could contribute to formulating voluntary goals to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from the military’. This is a start but more needs to be done and, importantly, the race to reduce GHG emissions must not lose sight of other environmental issues that must be addressed. These include those linked to the procurement and decommissioning of equipment, the management of the supply chain and the military estate, improving waste management, and the protection of the environment during military activities and missions.

Governments need to show leadership and commit to including the military as part of GHG reduction targets. To do this, we have set out what meaningful military GHG reduction commitments should entail. Your organisation can support this call here.

Linsey Cottrell is CEOBS’ Environmental Policy Officer, Eoghan Darbyshire its Researcher.

- Such as emissions due to infrastructure damage, conflict-linked environmental change, deforestation and post-conflict reconstruction – see CEOBS: How does war contribute to climate change?

- Data for 2021, and based on projections due to COVID-19.