Wartime geomorphological damage and geodiversity loss in Ukraine

Published: April 2025 · Categories: Publications, Ukraine

Since 2014, huge swathes of Ukraine’s geological heritage have been affected by fighting or militarily occupied, in many places causing irreversible damage to Ukraine’s landscapes. In this piece, CEOBS’ Rob Watson and Stella Shekhunova of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine examine the nature and extent of this loss of geodiversity.

Introduction

The living and non-living natural world are intrinsically connected. Geodiversity is the variability of geological formations, landforms and soils and, while it is the foundation of biological life, it receives far less attention.

Ukraine is rich in geodiversity, with geological strata spanning over three billion years of Earth history. The rocks of the Ukrainian Shield are the oldest in Europe and also host several meteorite impact structures. Sedimentary rocks in the lower Dniester basin deposited around 600 million years ago contain important examples of soft-bodied organisms, which were the precursor to the ‘Cambrian Explosion’ of life on Earth.1

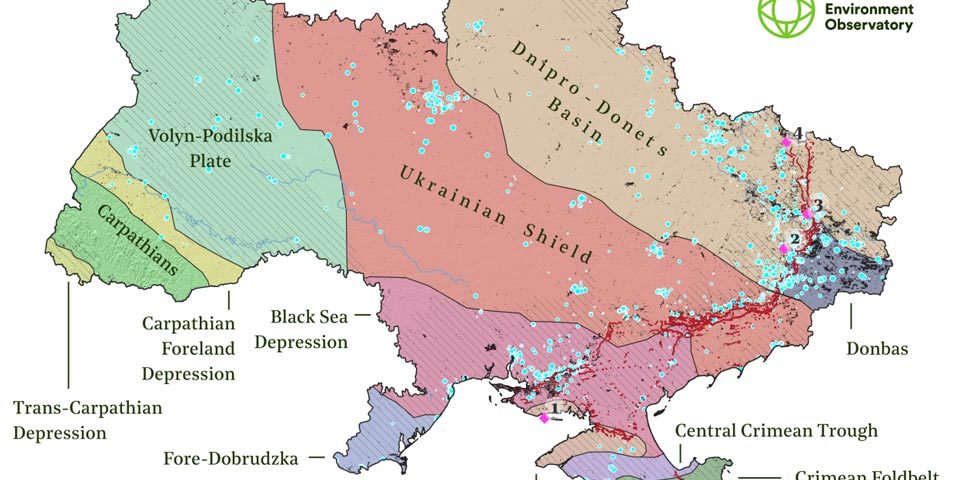

Alongside variation in rock composition, multiple phases of tectonic rifting, subsidence and uplift have created distinct geological zones in Ukraine. These include the largely low-lying areas of the Dnipro-Donets basin, which formed more than 300 million years ago and feature several large rock salt domes.2 The neighbouring Donbas region has a history of geological extraction and industry, being a rich source of coal and gypsum alongside other natural resources. These deposits are also highly fossil-rich and contain important information about ancient climates. There are also many upland regions, including the eastern part of the Carpathian mountains, near the border with Romania, and the mountains of sedimentary rocks along the southern coast of the also-occupied Crimean peninsula. Both ranges formed when the eastern European Alps collided with Turkey around 50 million years ago.3

The intersection of this geological diversity with a variety of climatic zones has formed a vast array of unique landscapes and associated ecosystems. Two of Europe’s longest rivers, the Danube and the Dnipro, end their journeys in Ukraine, flowing into the Black Sea, forming huge deltas with unique and protected wetlands and dune complexes. Other rivers form canyons cutting through bedrock, such as the Buzkyi Gard stretch of the Southern Buh and the Dniester Canyon between Ivano-Frankivsk and Chernivtsi. The latter area also hosts some of the world’s longest caves, unusually formed by rising groundwater in gypsum deposits. This has created multiple levels of underground mazes extending for hundreds of kilometres and hosting immaculate speleothems — cave structures formed by mineral deposition such as stalactites and stalagmites — crystals and sediments, which are all important records of past climates. Limestones, chalks and evaporite rocks are widespread in Ukraine, and many of these host karst landforms that have yet to be investigated in detail. Eastern Ukraine hosts steppe and semi-arid dune landscapes, and the shores of the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea host many important estuaries, beaches and peninsulas, forming the ‘Azov-Black Sea eco-corridor’. The protection of these landforms is a prerequisite for the preservation of Ukraine’s ecosystems.

Widespread damage to Ukrainian geoheritage

Just as with biological life, geodiversity is often a victim of armed conflicts. Russia’s occupation of Crimea and parts of eastern Ukraine since 2014, and its full-scale invasion in 2022, have resulted in extensive military damage to Ukraine’s geodiversity and geomorphology. Access to many areas remains difficult, meaning that remote assessments are often the only option for assessing the extent of this harm. This imposes limitations on what we can say with certainty about the effects of the war on geomorphology and geodiversity in Ukraine. However, remote observations allow reasonable inferences to be made about the likely consequences for Ukraine’s geological heritage and associated landscapes. We’ve focused on four key themes here where information was most readily available from analysis of four locations with important geodiversity close to the frontline.

Fire damage to rocks and soils

Soil profiles in Ukraine have been ravaged by explosive ordnance and associated cratering, sometimes termed ‘bombturbation’.4 Alongside bombturbation, landscape fires initiated at the firing points and impact sites of weapons are also a significant hydrological and geomorphological agent. The increased temperatures from burning accelerate mechanical weathering and chemically alter rock masses. This in turn leads to increased rockfall and erosion,5 and elevated concentrations of phosphorus and nitrogen in streams and rivers, with consequences for freshwater ecosystems, alongside degradation of soil organic matter, an important carbon sink. Due to the difficulties in restoring geological systems that may have taken billions of years to form, the functioning and value of geodiversity is especially vulnerable to fire damage.

By February 2025, fires had affected 13,600 km2 of Ukraine’s land mass; all of the sites focused on in this publication have been affected.6 The blackened chalk cliffs, crevasses and steppe uplands of the Dvorichansky National Nature Park in Kharkiv Oblast, which host understudied karst landforms and associated ecosystems and locally important glacial soils, are particularly visible examples of the effects of landscape fires on geodiversity. Another important case is the Kleban Byk Regional Landscape Park in Donetsk Oblast, which hosts spectacular petrified tree deposits dating from around 300 million years ago. There has been intense fighting there since 2022, and in February 2025 Russian media reported that their forces had assumed control of the area.

Fossil heritage destroyed

The fossilised Araucaria trees present in Kleban Byk were regarded as extremely well preserved and thus served as an internationally significant though understudied geological site.7 However, they are certainly not the only site of paleobotanical importance in Ukraine. A recent study reviewed the effects of the Russian invasion on Ukraine’s paleobotanical heritage. Alongside occupying and damaging many field sites such as Kleban Byk, Russian forces have destroyed and looted museums such as the Kharkiv University collection in Kamyanka, Kharkiv Oblast.8 Even away from frontline locations, these fragile specimens are at risk from aerial attack. The war has focused new attention on Ukraine’s fossil heritage from scientists outside Eastern Europe, who are beginning to better appreciate the significance of these collections.

Rivers altered and degraded

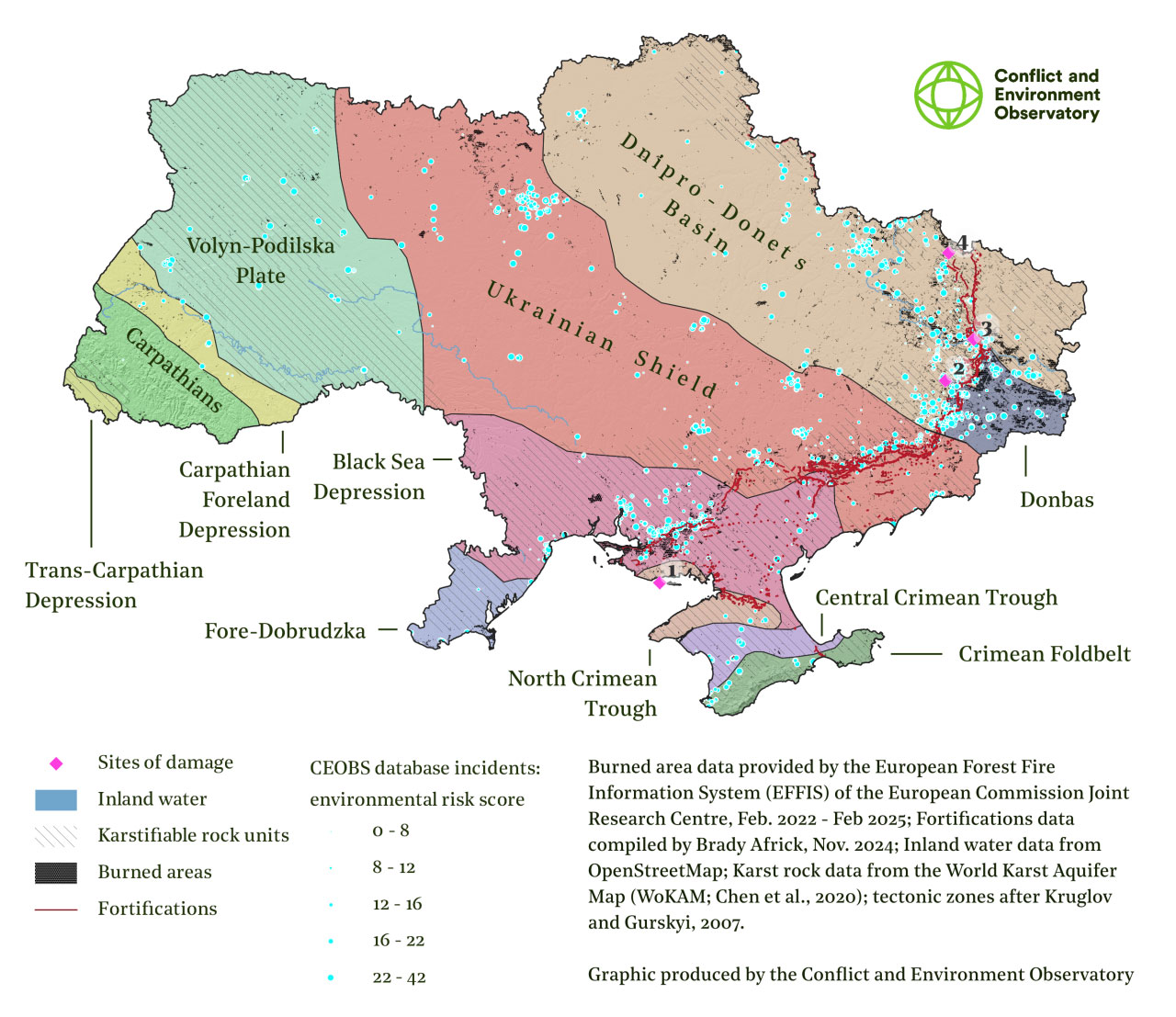

Natural landforms such as topographic ridges, depressions and valleys have long factored into tactical decisions in war.9 In Ukraine, several major rivers have become intense battlegrounds during the conflict. One example is a meander on the Siverskyi-Donets River at Bilohorivka in Donetsk Oblast. In May 2022, a Russian attempt to cross the river led to several days of intense fighting and the construction of military earthworks and three temporary pontoon bridges across the river. This was all abandoned once the battle ended, along with military vehicles and other debris. This debris has formed islands that are visible in satellite imagery, and bank erosion is evident from social media footage.

The Oskil river in Dvorichansky National Nature Park has also been the site of intense fighting. The park was occupied during the initial days of the Russian invasion in 2022 then partially liberated in Ukraine’s October 2022 counteroffensive.10 There has since been a frontline running the entire length of the park along the river valley. We received anecdotal accounts of the extent of geomorphological damage as of early 2025. Witnesses confirmed that two bridges across the river had been destroyed and that this debris, along with military equipment, was obstructing flow and altering the river bed. They also reported that the watercourse and some small lakes had been directly shelled.

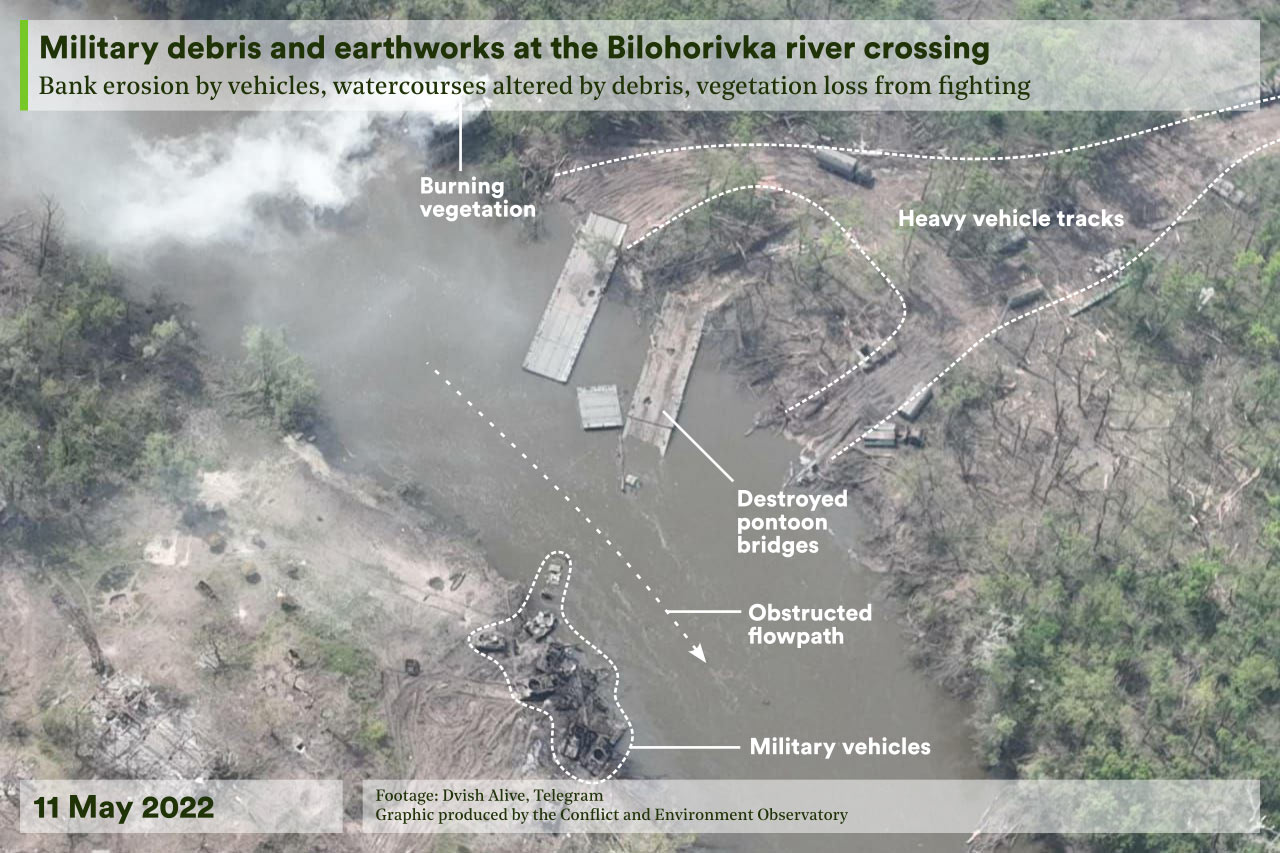

The 2022 invasion has led to the destruction of dams across several rivers and reservoirs, including the Irpin River, the Oskil River and the Karlivka Reservoir. Undoubtedly the most serious dam destruction occurred at the Kakhovka Dam in June 2023. This caused several days of unprecedented downstream flooding alongside upstream desiccation and renewed flow within a previously submerged channel in the former lakebed that pre-dates the reservoir’s construction. Models indicate that large quantities of submerged sediment were eroded, with sand deposits up to 3 m deep likely to have been mobilised alongside occasional larger cobbles. Furthermore, bank erosion and landslides in the lower Dnipro catchment have been mapped by researchers at the Institute of Geological Sciences of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine since the 2022 invasion (see below image), the effects of which have been compounded by continued fighting and detonation of explosive ordnance.

Coastal landforms under threat

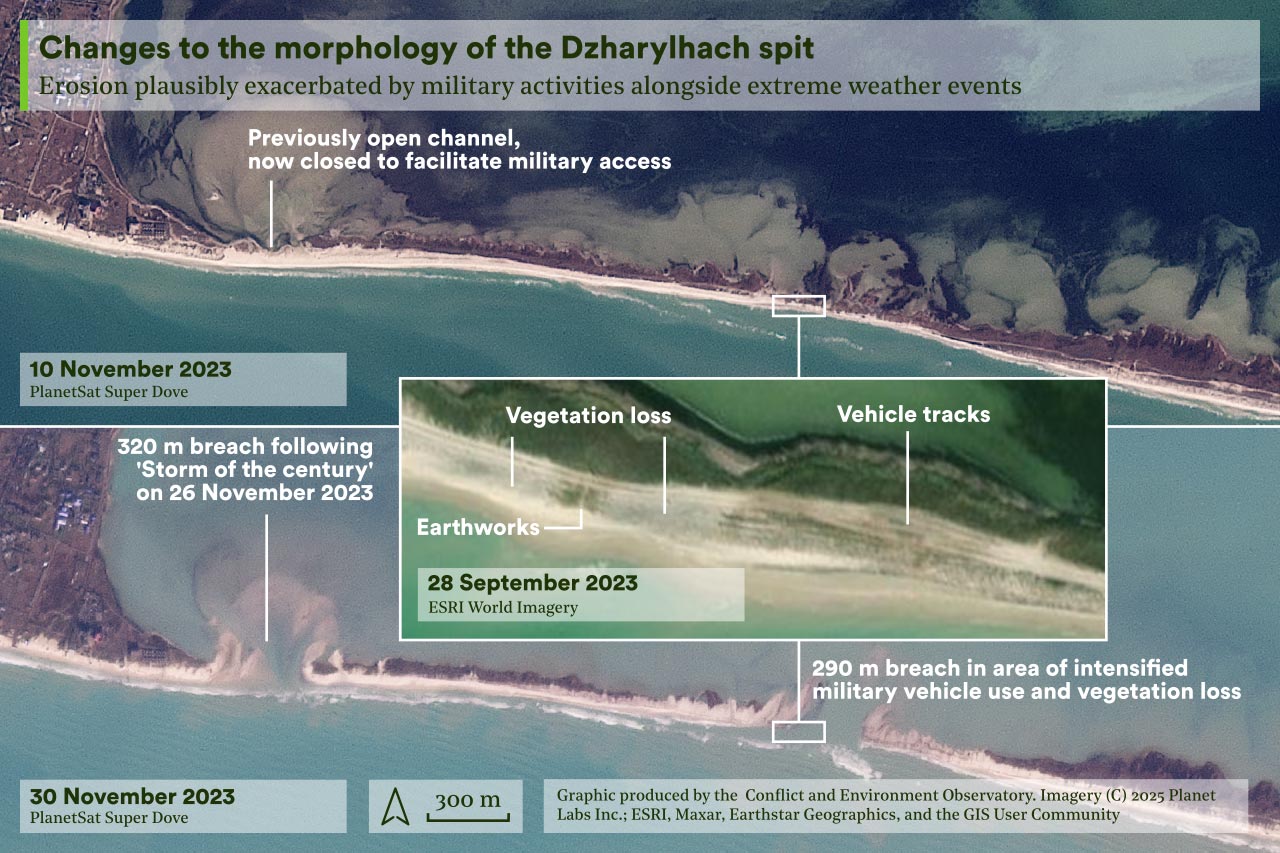

Ukraine’s extensive and understudied non-tidal coastal spits, channels and bays display a unique morphological variety. An example is the Dzharylhach Spit, which CEOBS investigated in an earlier briefing after Russian forces established a military base on the island at the spit’s eastern end. We identified military fortifications and vehicle tracks along the full length of the spit, combined with widespread landscape fires and vegetation loss. Furthermore, a pre-existing channel that breached the spit close to the mainland was closed by sediment build-up to facilitate military access. The loss of water exchange will have affected delta systems on either side of the channel that had only recently begun to be studied.

Erosion associated with a major storm in November 2023 reactivated the closed channel and also caused several new breaches. It is plausible that military activity increased the susceptibility of affected areas of the spit to breaching. The breaches in the spit remain present at the time of writing (March 2025). The long-term impact on sediment transport along the spit and associated biodiversity is likely to remain unclear now that access to the area is impossible, though analysis of satellite imagery does hold significant potential for understanding the spatio-temporal morphological development and its relationship to external factors.

Ukraine’s geodiversity must be better recognised and protected

Geologists have long sought to understand and protect Ukraine’s geoheritage, and Ukrainian scientists played an important role in the movement to preserve European geological heritage. Geoheritage in Ukraine forms a core part of the geological training provided at some universities and the country was the site of the first geological natural monument in the former Soviet Union, in the city of Dnipro. Despite this, many important sites of Ukrainian geoheritage and geomorphology have been threatened by industrial expansion since the mid-20th Century.11

Without strong advocacy and good governance, the pressures of war and the scale of the task of reconstruction will mean that geodiversity is overlooked once more. Landscape restoration in affected areas will take decades, incur considerable costs and is likely to be extremely complex to manage.12 Many landscapes also warrant additional protections to those that were in place before the invasion. Dvorichansky, for example, is not yet legally protected as an Emerald Network site, which would afford it protections under the Bern Convention. A 2016 study appraised the geological heritage of the area and earmarked it as a potential UNESCO Geopark site. Similar work in Dnipropetrovsk Oblast identified four further candidate sites.

Official recognition of the geological value of these sites alongside their ecological value would help to strengthen restoration efforts and create parallel environmental benefits. In Ukraine, the Nature Reserve Fund governs the creation of new sites where nature, including geological heritage, is protected, though the exact legal protections awarded to geological heritage are only vaguely described. Additionally, Ukraine is a signatory to several international agreements that could be employed to pressure and obligate authorities to protect geodiversity, though again the language in these does not directly refer to geological heritage.

Looking ahead, the first step towards providing renewed access to and appreciation of Ukraine’s geological heritage should be to rigorously assess the legal and environmental status of existing and candidate sites. Although site access in frontline and occupied areas is still impossible, the process can be begun remotely. For example, recent work has shown that it is feasible to model the sensitivity of an area’s geodiversity and geomorphology to the effects of landscape fires within a Geographical Information System. An updated inventory of sites of geological heritage and their legal status would be an integral part of such work and would need further development and collaboration between researchers, local authorities and communities across the country.

Rob Watson is a Junior Researcher at CEOBS; Prof Stella Shekhunova is the Deputy Executive Director of the Institute of Geological Sciences of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

- For more details, see: Dzik and Martyshyn, 2015; Nesterovsky et al., 2018; Soldatenko et al., 2019a; Soldatenko et al., 2019b.

- For more information, see van Hinsbergen et al., 2015.

- The river and stream network associated with ongoing mountain building in the Carpathians forms a valuable ‘natural laboratory’ for testing theories about landscape evolution, investigated by Gailleton et al., 2021.

- See Certini and Scalenghe, 2024 for an overview of the effects of warfare on soils. A 2023 report by EcoAction provides information on soil health across Ukraine since 2022, and Leal Filho et al., 2024 provide an overview of the effects of the war on soils in a selection of Ukraine’s protected areas.

- The impacts of wildfire-triggered rockfall on the geological and cultural heritage associated with rock climbing were studied by Yeste-Lizán et al., 2023.

- To estimate areas affected by fires, we used burnt area maps derived from Sentinel-2 and MODIS imagery by EFFIS (European Forest Fire Information Service) for Ukraine from February 2022 – February 2025.

- The trees at Druzhkivka were originally discovered by workers who were mining the stone to build a factory in the 1920s. Their scientific significance was only fully appreciated in the 1970s, when they were registered as a site of geological heritage. Although many hundreds of examples were originally present at the site, only a few dozen now remain due to looting of the site for building materials and for illegal trading. The only other known site on earth containing petrified trees of a similar age is located in Arizona and is far better studied.

- To read this article, see p.12 – 14 of the Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference and XLI Session of the Ukrainian Paleontological Society, which took place in Kyiv in October 2023.

- See, for example: Doyle and Bennett, 2002; Guth, 2011; Häusler, 2020; Gleick and Shimabuku, 2023.

- Scientists continued to monitor the landscape during the initial occupation in 2022 and park rangers have spoken about their experiences during that period; at present park staff are not able to collect information on the ground due to intensified fighting since 2024.

- Examples include attempts to build hydroelectric dams across the Southern Buh in Buzkyi Gard, which have thus far been resisted, and poor hydrological management of the Danube Delta since the 1950s, where rewilding has sought to mitigate the earlier effects of multiple barriers and dams.

- The most responsible remedial actions to take are not always evident: mechanical demining operations may exacerbate soil erosion, for example.