This is the seventh in a series of thematic briefings on the environmental consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, jointly prepared by the Conflict and Environment Observatory and Zoï Environment Network. This work is supported by the United Nations Environment Programme as part of its efforts to monitor the environmental situation in Ukraine.

Situation

The scale and intensity of the conflict in Ukraine has resulted in widespread and locally severe damage to some of its most ecologically important areas, while many others remain occupied. The conflict is impacting Ukraine’s biodiversity through a range of both direct and indirect means, with threats such as landmines and explosive ordnance creating risks that will last decades. The severity of the damage to landscapes is encouraging consideration of approaches such as rewilding. While this could help Ukraine meet its international obligations for nature protection, societal buy-in will be needed if nature is to be successfully embedded in Ukraine’s recovery.

Contents

Overview and key themes

Biodiversity conservation in Ukraine before February 2022

Ukraine occupies less than 6% of Europe’s land area, but because of its significance for migratory species and geographic diversity, possesses 35% of its biodiversity. This equates to more than 70,000 species, including many that are rare, relict or endemic.

The percentage of Ukraine’s territory – including Crimea – that enjoyed protection under defined national legislation increased from 4.6% in 2004, to 6.8% today, which is low by EU standards. In this briefing we use the term protected area for an area that enjoys legal recognition, and the catch-all ecologically important area, as an area of importance for biodiversity, irrespective of legal status. Ukraine’s 6.8% total excludes the Emerald Network, a prospective protected area network and part of the Bern Convention, although there is some overlap.1 Ukraine has ratified the convention and is in the process of creating and legislating for Emerald Network sites.

Ukraine has 50 Wetlands of International Importance, and eight UNESCO Biosphere reserves. Researchers had identified 142 Key Biodiversity Areas, although 59 of these were outside formal protected area boundaries, with just three fully covered. Transboundary areas of ecological importance span Ukraine’s borders, including the Danube Delta, which is shared with Moldova and Romania, Polissya, shared with Poland and Belarus, the Dneister basin, shared with Moldova, and the Carpathians, shared with Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia.

Before February 2022, Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and occupation of parts of the Donbas, had heavily impacted biodiversity protection in some of Ukraine’s most important protected areas. In Crimea, this included six of Ukraine’s 19 IUCN 1A nature reserves. In Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts, nearly one third of protected areas were behind the front line. Damage to sites in the Donbas was widespread, and included 78 nature reserves, wildlife sanctuaries, and landscape parks. Of these, 50 protected areas had experienced fires, 29 had been directly affected by hostilities and fortification construction, and six had suffered from the illegal extraction of natural resources.

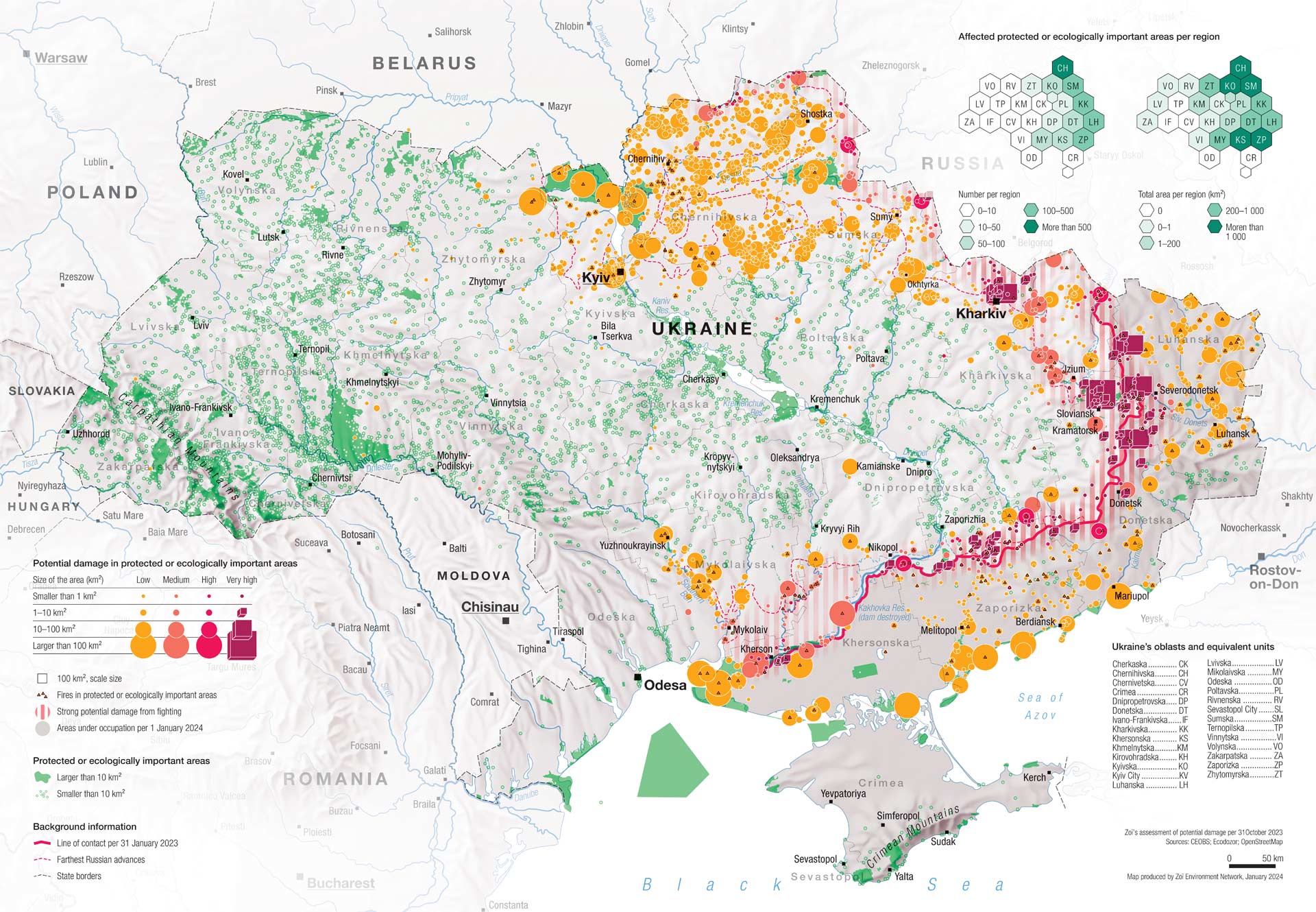

Damage to Ukraine’s ecologically important areas since February 2022

Nationally, around 2,000 protected areas had been either temporarily occupied, or remained occupied at the end of 2023. This reflects the geographic scale of the armed conflict, and in particular its long frontlines. As a high intensity mechanised conflict, which has seen the intensive use of explosive force, damage to landscapes and habitats has been widespread and locally intense. Ukraine’s steppe ecosystems in its south and east have borne the brunt of the damage, placing their plant and animal species at particular risk. Conservation programmes on landscape-level projects to connect habitats and protected areas have also been hard hit.

The destruction of water infrastructure such as the Oskil and Kakhovka reservoirs has impacted freshwater ecosystems, both through downstream flooding and through desiccation. While naval warfare has been less extensive than feared, military activities have damaged coastal and marine habitats. We addressed this in an earlier briefing.

In common with the conflict’s environmental dimensions more broadly, its impacts on nature and ecosystems have received comparatively greater attention than is typical. In spite of this attention, determining the precise impact on habitats and species remains complex. Ecosystems must be monitored over more than one season, by experts with knowledge of them, yet in many cases ground surveys remain impeded by frontlines, the presence of landmines and explosive ordnance, and the loss of human capacity and equipment. To date, preliminary surveys have been undertaken at some sites by park staff and civil society organisations, but these have been constrained by the circumstances of the conflict. It is possible that, for some sites, the true extent of the damage wrought by the conflict will never be known.

Physical damage to ecologically important areas since February 2022

Based on proximity to the shifting front lines, and on Ecodozor data, around 7.5% of Ukraine’s areas important to nature can be expected to have suffered moderate to significant damage. Many have been temporarily occupied, or remain so, with around 19% of ecologically important areas still beyond government control. Others have, for varying lengths of time, become the front lines in the conflict. The physical implications of proximity to frontlines are diverse. They include blast damage from the use of explosive weapons, which can include cratering, vegetation loss and the dispersal of shrapnel and toxic munition compounds. Where explosive weapons impact water bodies, aquatic organisms can be affected by acoustic shock.

Mapping damage along frontlinesRemote monitoring of environmental risks during conflicts tends to focus on individual facilities. However, predicting the likely damage to larger geographic areas can be valuable for highlighting potentially damaged locations. Such approaches can be particularly useful where the areas in question are sparsely populated, which can translate into fewer reports of damage via social or traditional media. Within Ecodozor, the potential damage from armed hostilities (and which was used for the map above) is assessed for each area by:

The closer to the front line, the longer the period and the more shelling recorded in the vicinity, the more likely it is that damage to land, nature and infrastructure can be expected in a given area. For the purpose of our spatial damage assessment, Ukraine is divided into 100 ha plots. The intensity of hostilities is calculated based on Ecodozor data supplemented by those from ACLED (Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project). The sum of reports of hostilities within a 20 km radius is calculated for each area.2 Similarly, proximity to the front line is calculated for each area as the sum of the daily risk factors. As shelling far from the front line is unlikely to cause widespread spatial damage, areas where the proximity indicator is very low are filtered out. A combined value of a potential damage to an area is then calculated, using the highest values for intensity and proximity. |

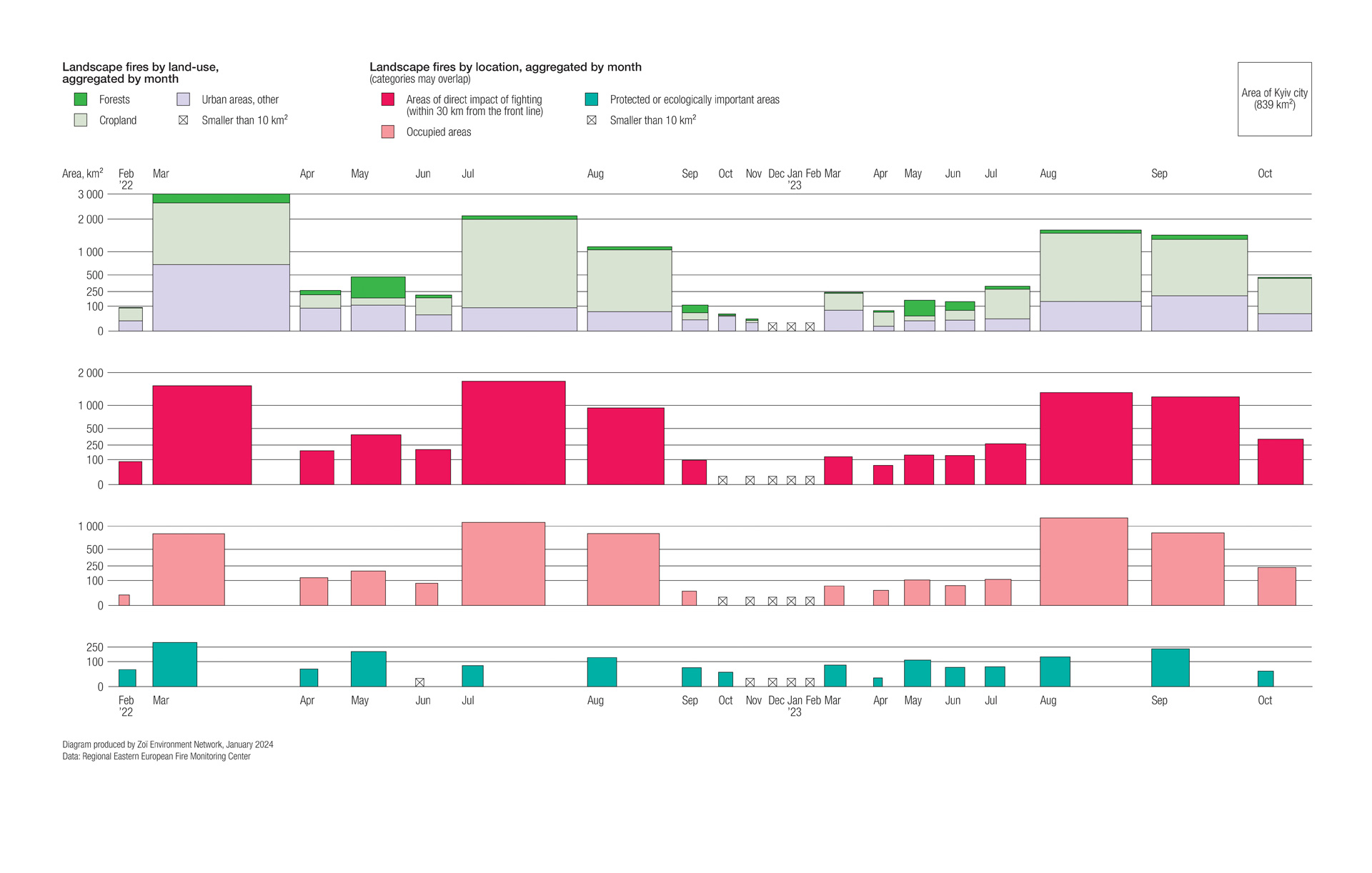

Landscape fires can be initiated at the firing points and impact sites of weapons. By the end of October 2023, fires had affected 12,000km2 of the country, with 75% of these occurring within 30km of the frontline. Analysis indicates that 1,650km2 of the area affected by landscape fires was classed as ecologically important. Cratering and fires can leave landscapes more exposed to erosion, and to colonisation by invasive species. Vegetation loss reduces habitats and food sources.

In national parks and other formally protected areas, park infrastructure has been destroyed by shelling, with the consequent loss of equipment and records. The laying of mines and booby traps, and the dispersal of explosive remnants of war creates hazards for people and wildlife, and has impeded access for researchers. Toxic remnants of war are also a problem where fighting has been intense, and include munitions residues, fuels and oils, military waste and contaminated military scrap. Acoustic pollution and disturbance from fighting and vehicle movements disrupts wildlife feeding and breeding patterns.

Military vehicle movements can accelerate erosion or lead to soil compaction. Vehicle emplacements, trenching and the construction of earthworks also contribute to erosion, as well as change drainage patterns, damage root systems, interfere with wildlife movements and disrupt habitats and vegetation assemblages.

Ukraine’s geodiversity at risk

Geodiversity encompasses geological formations, landforms and soils, and while it is the foundation of biological life, it receives far less attention. Just as with biological life, geodiversity can also be a victim of armed conflicts.

Ukraine is rich in geodiversity: the rocks of the Ukrainian Shield are the oldest in Europe, and host several meteorite impact structures. The Ukrainian Shield has vast expanses of steppe and freshwater lakes. Some of the world’s longest gypsum caves can be found in the west of the country, and the coast around the Tarkhankut Peninsula on the Black Sea hosts spectacular cliffs and sea stacks. Ukrainian geologists have long sought to protect the country’s geoheritage: the country was the site of the first geological natural monument in the former Soviet Union, in the city of Dnipro. Geoheritage in Ukraine is legally protected in many areas and forms a core part of the geological training provided at some universities.

Since 2014, huge swathes of this geological heritage have been occupied or affected by fighting, in many places causing irreversible damage to Ukraine’s landscape. Among the lands on which ground fighting has taken place are the chalk steppe of the Dvorichna National Park, the coastal estuaries of the Meotyda, Azov-Syvash and Pryazovski national parks, which border the Sea of Azov, and the semi-arid dune environment of the Oleshky Sands National Park. These fragile landforms host many unique and rare flora and fauna, and their protection is a pre-requisite for the preservation of Ukraine’s ecosystems.

Indirect harms to ecologically important areas since February 2022

Beyond the physical impact of the fighting, indirect and reverberating effects have also impacted ecologically important areas, and their management. Some areas may have benefitted from reduced human pressure due to their closure for security reasons, although in others reduced oversight from the authorities may have increased the potential for illicit resource extraction. The conflict has reduced firefighting capacity and access in rural areas, together with regular measures to reduce wildfire risks. The vast quantities of unexploded ordnance not only obstruct access for firefighters, they also remain a source of ignition.

Conservation programmes and researchers have been heavily impacted by the war, with projects paused or cancelled, and experts displaced internally or overseas, or called to serve in the armed forces. Martial law has limited public access to environmental information, as well as to the landscape itself, impeding independent monitoring. The experience of other conflict-affected areas suggest there is a considerable risk that nature protection will be sidelined during reconstruction and recovery. Unless measures to improve nature protection are fully integrated into recovery planning, reforms to the planning system to expedite recovery could have detrimental effects on areas of ecological importance. This is also the case for changing patterns of land and infrastructure use. Increased pressure from shipping in the Danube Delta in response to the blockade of Black Sea ports is an example of how such wartime shifts can impact areas far from the front lines.

In response to the conflict, conservation actors strengthened or expanded their networks, often drawing on regional or diaspora expertise. Efforts to map Ukraine’s ecologically important areas were accelerated, while technical and donor support has been important for sustaining or reorienting activities in some areas, including for NGOs gathering data on harm to nature on the ground. While the conflict has had a substantial impact on conservation governance at the state level, it has not prevented the opening of three new nature parks, some have argued that the relationship between the land and patriotism could have a lasting impact on Ukrainian nature protection values.

Loss of nature protection in areas occupied since February 2022

The personnel and property of protected areas that have been, or which remain subject to occupation, have been profoundly affected by the conflict. The director of the Kamianska Sich National Park in Kherson Oblast was reportedly captured and interrogated before escaping. The park was subsequently desiccated by the draining of the Kakhovka reservoir. Looting of park equipment has reportedly been common during periods of occupation, this includes the loss of vehicles, watercraft and drones, as well as computers and office equipment. For some areas, staff have been able to continue their research and management activities, even under occupation and the stresses associated with it. The Holy Mountains National Park authority took on some roles of the state in supporting the communities that live around it, this included the provision of firewood.

The internationally known Askania-Nova UNESCO Biosphere Reserve in Kherson Oblast has been under occupation since the first day of the invasion. For a year, staff remaining at the site were reliant on public donations gathered by the Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group, before the Russian authorities announced its legislative transfer to Russian control. Since then, some of its animals have been transferred to Russian zoos. Prior to 2022, the de facto authorities in occupied areas of the Donbas worked to create the impression of biodiversity governance, but it is extremely unclear to what extent protected areas currently under occupation are being managed to benefit nature. The self-styled Donetsk People’s Republic recently claimed that it would create three new national parks, including one on part of the territory of the Holy Mountains National Park, which is back under Ukrainian government control.

Prospects for nature during recovery

Concern over the impact of the full-scale invasion on some of Ukraine’s most important ecosystems has encouraged attention on the potential role of nature recovery within Ukraine’s wider recovery policies. Such considerations are set against Ukraine’s biodiversity goals and obligations. These include the goal of protecting 30% of its territory by 2030, the biodiversity targets associated with EU alignment, as well as the needs of climate adaptation and mitigation. The EU has proposed funding for nature and biodiversity conservation as part of a wider package of recovery measures.

The proposed nature recovery measures are diverse. At the practical level, these include the reinstatement of the human and material capacities of liberated protected areas, coupled with the limited explosive ordnance clearance activities necessary to restore partial access to them. On the legislative level, one focus area should be the ongoing work to legally designate new areas that are part of the Emerald Network, as well as introducing NATURA-2000 legislation.

The realities of the conflict, and the scale of the destruction it has caused, has also focused attention on the potential role of rewilding – giving over severely degraded lands with high levels of explosive ordnance contamination to nature. Many of these areas include formerly productive agricultural lands. Ukraine is no stranger to rewilding, with projects on the Danube Delta and the Chornobyl Exclusion Zone pre-dating 2022. The cost of reinstating damaged land, the opportunity for Ukraine to reconsider its historically intensive land use policies, and to meet its international biodiversity obligations and EU alignment targets, make rewilding an obvious nature-based solution. However, the idea that explosive ordnance contamination be left is extremely controversial as it would conflict with Ukraine’s clearance obligations under international treaties.

Clearing mines in ecologically sensitive areas

Clearing mines and explosive ordnance had been underway since long before February 2022, this includes legacy contamination from WWI and WWII. It is coordinated and partially executed by the Ministry of Defence, the Special Transport Service and the State Emergency Service, and supported by a variety of commercial and humanitarian operators. Absent precise data on the extent of contamination, and with the problem still growing, it is estimated that around 30% of Ukraine’s territory is affected. This includes substantial areas of ecological importance, as well as agricultural land, coastlines and forestry.

Various clearance goals have been proposed, from 80% of contaminated territories being returned to normal use within 10 years, as part of the President’s Peace Plan, to the Cabinet of Ministers’ more realistic estimate of 70 years for full clearance.

Irrespective of the pace of clearance, which may cost billions, areas will be prioritised based on the risks posed to communities and to their societal and economic value. Natural areas will inevitably be a lower priority than agricultural land, and perhaps even forestry. Without a conscious decision to earmark funding and capacity to clear them, contamination of ecologically important areas may last decades, and restrict the use of many of their services, including for eco-tourism.

Moreover, there are already indications that war remnants will influence land use, potentially to the detriment of nature. For example, contamination of agricultural land with mines and explosive ordnance can drive agricultural expansion onto grassland or shrub ecosystems, as this may be cheaper and quicker than clearance. Such areas were already under pressure and so this would exacerbate a pre-conflict trend.

Demining can be environmentally damaging. Mechanical demining, which uses vehicles to destroy mines in the soil reduces time and costs but can damage soils, disperse pollutants and accelerate erosion. Even where mines are removed by hand, this typically requires the cutting of vegetation, and generates pollution, whether mines are destroyed in situ, or gathered for bulk field destruction. Where mines and explosive ordnance have been present in the environment for long periods, as seems likely with Ukraine, their removal can be more damaging to soils and vegetation.

While some NGO operators active in Ukraine have environmental policies, these are relatively new to the sector. A national standard that helps protect the environment and which applies to all state, private and NGO mine action actors in Ukraine is yet to be developed but would contribute to reducing environmental disruption to the third of Ukraine’s territory that is affected. It should be complemented by dedicated programmes to assess and prioritise environmentally sensitive clearance methods in forest and natural areas, tailored to Ukraine’s diverse ecosystems. Dedicated clearance mandates and capacities for state entities responsible for environmental protection, including the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources, and its State Forest Service, would also be valuable.

Discourse on rewilding in Ukraine during wartime has also encouraged consideration of whether nature can help protect the country militarily. This so-called “defensive-wilding” is understood as including everything from planting vegetation along key transport routes to provide cover for defenders, to giving over large swathes of explosive ordnance and mine-contaminated borderlands to nature to confound attacks from neighbours. Thick natural vegetation, mires and peatlands are considered a far greater obstruction than agricultural land.

The debate has been further intensified by large-scale incidents, such as the draining of the Kakhovka and Oskil reservoirs. Their loss has opened up the space for conservationists to draw attention to the damage that dam construction has historically caused to Ukraine’s riparian ecosystems, and the opportunities for the restoration of important habitats. But as with nature recovery more broadly, prioritising nature in such cases can conflict with existing and emergent resource use interests, as well as with economics and politics.

While the discourse has often focused on the potential for policies like these to benefit nature, or local economies, the potential of nature restoration projects to support Ukraine’s psycho-social recovery and healing should also be examined.

Case study: The militarisation of Dzharylhach National Nature Park

Dzharylhach National Park is a protected area on Ukraine’s largest island. It is connected to the mainland at low tide by a long sand spit that creates a sheltered bay, flagged by around 200 estuarine lakes. The park sits in the ‘Karkinitska and Dzharylgatska Bays’ Ramsar wetland of international importance, which is also an Important Marine Mammal Area.

Video from the GEF Small Grants Programme project “Mainstreaming biodiversity conservation on steppe landscape” introduces the Dzharylhach National Nature Park’s ecosystem and biodiversity prior to the current conflict.

Dzharylhach is characterised by diverse vegetation, with 28 plant communities of different salt-tolerant and dry-adapted species, which are highly vulnerable to sand movements. These include 54 endemic and sub-endemic species, which collectively represent 11% of its flora. Many rare and endangered birds, insects and snakes that are listed in Ukraine’s Red Book are found on the island, as well as introduced mammals, including deer, wild boar, hares and wild dogs. The bay is an important area for bottlenose and common dolphins, harbour porpoises, sturgeons, beluga, rare crustaceans and molluscs. Dzharylhach even holds the record for the northernmost sighting of the loggerhead sea turtle. The area has been occupied by Russian forces since early March 2022.

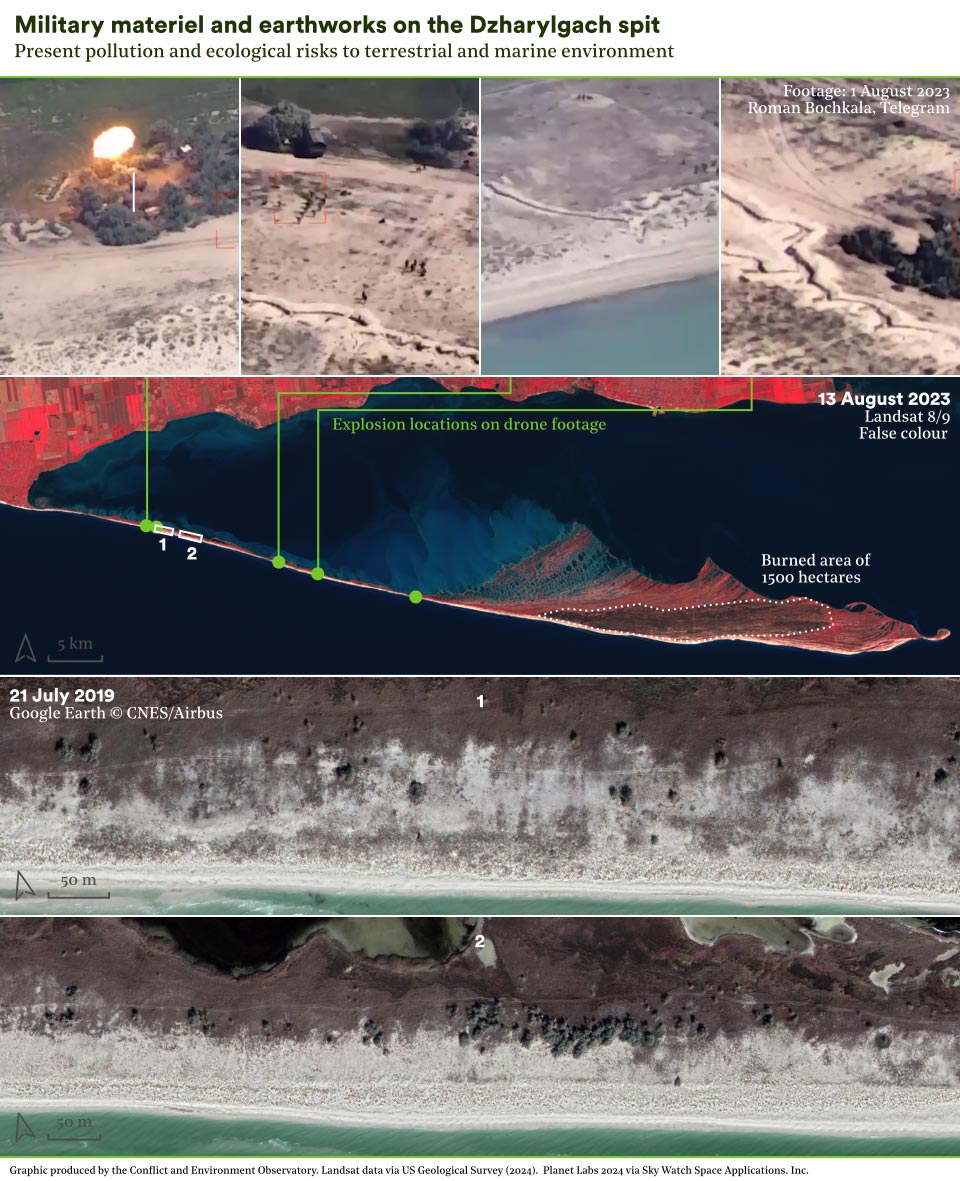

Although Russian occupying forces released plans to use Dzharylgach for hunting, fishing and tourism, as well as clay and salt mining, it has instead been converted into a military training ground. The Ukrainian military has suggested that the site now hosts around 300 newly mobilised soldiers at any time, that there are warehouses of vehicles and ammunition, and that the ecologically sensitive area was chosen deliberately so as to shield it from Ukrainian attacks.

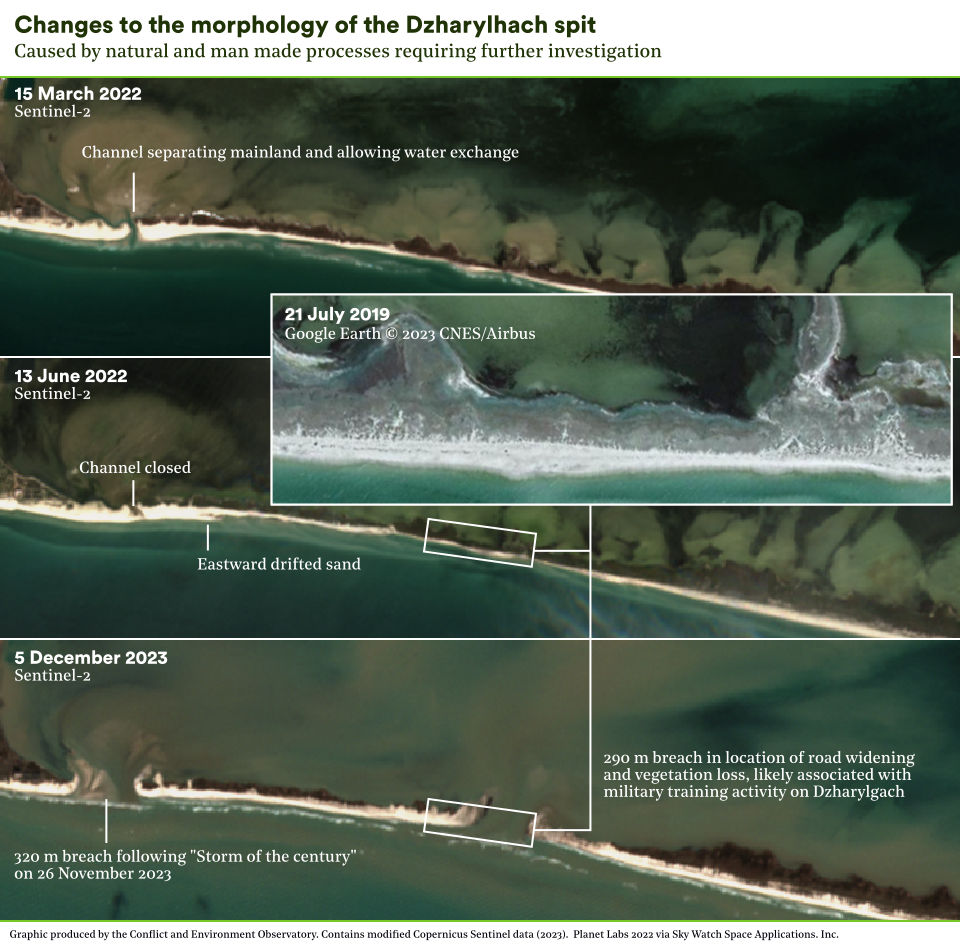

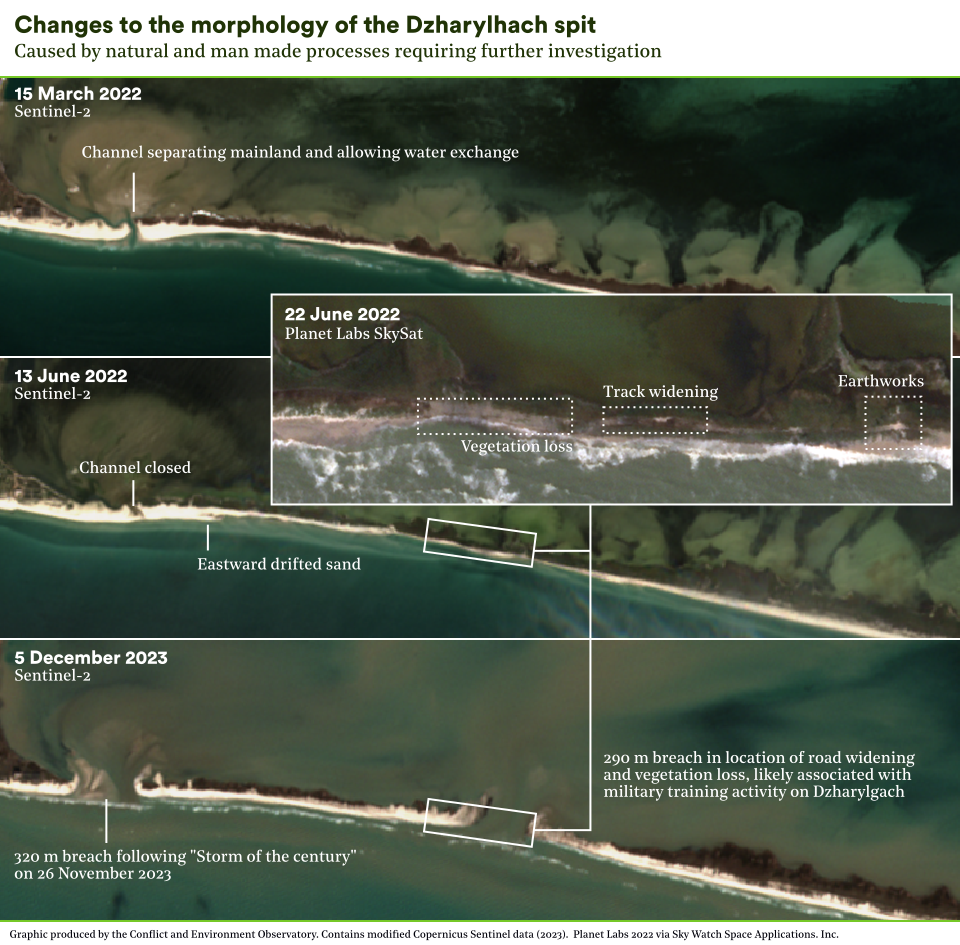

Until late May 2022, a narrow channel separated Dzharylhach’s spit from the mainland and allowed water exchange between the Black Sea and Dzharylhach Bay. After this time the channel was closed, allowing vehicle access from the mainland and posing multiple risks to the bay, including siltation, eutrophication, and deterioration of the habitat for cetaceans. It was reported a year later that the channel was closed intentionally by Russian forces. Whilst this is certainly possible, it must also be noted that the channel is dynamic with changes in morphology year-on-year. The channel has previously closed naturally,3 and there is evidence of sand drifting elsewhere.

Recent satellite imagery reveals significant earthworks along the spit, including trench complexes, revetments, bunkers and many craters. Earthworks in such a sensitive location impact vegetation and root systems, wildlife movements and, given the island’s high winds, erosion. The main access track along the spit has been widened and vegetation removed, whilst heavy vehicle tracks are visible alongside. Drone footage from August 2023 revealed these trenches in detail, as well as multiple military vehicles and troops, before then showing HIMARS missile attacks on them. Such incidents, including similar attacks along the coast,4 are likely to result in further environmental damage.

It can be anticipated that military training exercises may have caused soil and water pollution from toxic munitions residues like RDX and TNT, from fuel, lubricants and other chemicals from military vehicles, as well as from litter and waste from human occupancy. Furthermore, acoustic pollution from military activities is of concern given the impact it may have on the high concentrations of dolphins and porpoises in the bay.

In August 2023, a fire burnt around 1,500 hectares, nearly half of Dzharylhach island. It was detected from space between 4 – 7 August, with smoke plumes visible from across the bay in Skadovs’k. The day of ignition had a low fire weather danger, increasing the likelihood that it was of military origin. Furthermore, although fire is a natural phenomenon for steppe ecosystems, satellite observations show fires on this scale are unprecedented for Dzharylhach in at least the last 24 years.5 Small-scale burns have been reported in the past, with the park authorities able to respond, something that is impossible now due to the military presence.

It is expected that the fire significantly impacted small land animals unable to escape, some of which are listed in the Red Book of Ukraine, such as the steppe viper. Vegetation was also damaged, including rare species of grasses, a loss of food and shelter for wildlife. Deep roots and bulbs can offer fire-resilience, but this is reduced where soils are damaged by military vehicle movements or disturbance. Following the fire, Ukraine’s Ministry of the Environment and Natural Resources described the entire protected area as having been destroyed.

On November 26, 2023, Storm Bettina, locally referred to as the “Storm of the century”, brought near-record low pressure,6 hurricane force winds, large waves and a strong tidal surge. The storm breached the spit in three places, two of which are locations identified as having had a significant military footprint. This may be a coincidence, as there were also breaches in the Tendra spit further west, but there remains a possibility that the military activity weakened the spit structure. The storm surge likely transported military pollution from the land into Dzharylhach Bay, as was also reported in Crimea. The eventual impact of the storm damage remains unclear, but could ultimately prove positive if it stops the use of the area for military training.

Dzharylgach has been impacted in multiple ways from the establishment of a military training base, together resulting in potentially significant harm to ecosystem function, biodiversity and geodiversity. A ground assessment will be required for the full magnitude of any damage to be uncovered but this is prevented by the ongoing military occupation. No Ukrainian scientist has had access to the area for nearly two years, nor have there been regular checks on veterinary health, as previously undertaken. The site is also likely contaminated with explosive ordnance, assuming it is a low-priority for clearance, this will be a further barrier to surveys or tourism income upon liberation.

Immediate and future needs

Ukraine’s ecologically important areas continue to be heavily impacted by the conflict, and in some areas the loss of species or habitats will be permanent. The true extent of ecological harm remains unclear, even if the impact of the conflict on Ukraine’s capacity for biodiversity protection is becoming more apparent. As with climate change adaptation and mitigation, recovery from the conflict presents opportunities to enact policies that encourage a greener future. Nature recovery should be viewed as a priority, because of the benefits it can bring to Ukraine’s society and economy, as well as to its biodiversity.

Restore protected area administrations

Restore the human resources and technical capacity of protected area administrations, and ensure sufficient levels of safe physical access to parks and reserves.

Develop nature monitoring strategy

Develop a monitoring strategy to document the immediate and long-term impacts of the conflict on ecologically important areas. This should encompass baseline data, accessing local knowledge, remote assessment, field assessments and participatory research methods. A parallel strategy should be developed for the remote monitoring of ecologically important sites in areas subject to occupation.

Update environmental mine action standards

Develop and implement national mine actions standards for environmentally sensitive clearance. This should be complemented by policy guidance addressing the prioritisation of clearance for legally designated and non-designated areas of ecological importance.

Ensure a nature positive recovery

Develop a national strategy for a nature positive recovery in Ukraine, which embeds nature, and nature-based solutions, across government policies. The strategy should be sensitive and responsive to the direct and indirect threats to nature being created or exacerbated by the conflict, and be guided by Ukraine’s biodiversity obligations, including 30×30. Public engagement is important and the policy’s aims and implementation should be informed by citizen assemblies and other inclusive formats, to ensure that it is responsive to the needs of Ukrainian society.

Media enquiries: doug(at)ceobs.org or nickolai.denisov(at)zoinet.org

Research and content by CEOBS and Zoï Environment Network.

Thank you to our additional contributors and reviewers: Oleg Dyakov (Rewilding Ukraine), Olesya Petrovych (Reform Support Team of the Ministry of Environmental Protection and Natural Resources of Ukraine), Hanna Plotnykova, Oleksiy Vasyliuk (Ukrainian Nature Conservation Group) and Sergiy Zibtsev (National University of Life and Environmental Sciences, Kyiv).

Cartography: Matthias Beilstein, Zoï Environment Network, Schaffhausen. Graphics: Matthias Beilstein and Eoghan Darbyshire, CEOBS.

- The calculation is complicated as the boundaries of existing legally designated protected areas and prospective Emerald Network sites overlap in places, for further discussion, see the report on our mapping project: https://ceobs.org/mapping-ukraines-ecologically-important-areas

- Using the PHP programming language, the PostgreSQL relational database management system and the PostGIS spatial information processing module.

- Based on an inspection of Landsat imagery in Google Earth, the channel was closed in 1991, 2000, 2001, and 2002.

- A video purporting to show damage to military infrastructure on Dzharylgach has actually been geolocated to two locations further west along the coast – first location is at 46.122, 32.267 and the second is at 46.132, 32.222.

- Visual inspection of the MODIS Burned Area product on FIRMS for each year 2001-2022 showed no burned area pixels over Dzharylgach island.

- Generated by anomalously high temperatures in the eastern Mediterranean. There has not yet been any climate attribution on this storm system to say how much more likely or severe it was because of climate change.