33 participants create seven citizen science projects to help address war-related water quality issues in Ukraine.

As part of the GROMADA project CEOBS developed and hosted an online hackathon to identify citizen science opportunities to track water quality issues linked to the war in Ukraine. In this post, the team report on the event and its results.

The war on Ukraine’s water quality

Armed conflicts disrupt water systems that are critical for human wellbeing and environmental safety, and since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, CEOBS has been documenting incidents of environmental harm, including to critical water and energy infrastructure. During wars, water pollution may stem from a number of direct and indirect sources. In Ukraine this includes the toxic remnants of weapons, leaks and discharges caused by attacks on industrial facilities, or a lack of infrastructure maintenance, such as to mine tailing dams, as well as from acid mine drainage from closed or de-energised coal mines. Environmental harm may occur within various parts of the hydrological cycle, including surface waters — such as rivers and lakes, groundwater aquifers or the marine environment.

Damage to water systems in Ukraine has been the most extensive along the frontline, although regions beyond are also affected by indirect impacts, such as power cuts and the pressure caused by the relocation of enterprises and people. The east and south of Ukraine are home to many metallurgical, chemical and agricultural enterprises and have long been dependent on large-scale water infrastructure such as dams, canals and reservoirs. Even before 2022, the region was affected by climate-linked water scarcity, legacy industrial pollution and ageing infrastructure; in places, the war has made the situation critical. For example, in early 2022, fighting cut the water supply to 450,000 people in the city of Mykolaiv. In June 2023, the destruction of the Kakhovka Dam left around 1,000,000 people without access to safe water, requiring huge investments to establish emergency pipelines.

In some cases, citizen science initiatives have stepped in where state water monitoring capacities have been overstretched, helping monitor water or identify sources safe for emergency use. After a Russian missile strike on the Karachunivske Reservoir’s dam in September 2022, local authorities used iron quartzite waste rock to stabilise the breach; downstream water turned red. A local citizen science initiative Stop Poisoning Kryvyi Rih countered disinformation and helped to prevent panic by doing tests and proving that there was no immediate danger from a short-term increase of iron content.

The water quality hackathon

CEOBS is a partner in the Erasmus+ funded GROMADA project, which aims to foster cooperation between academia and civil society to address war-related environmental damage in Ukraine. GROMADA’s focus is on the potential role of citizen science in Ukraine and as part of the project three themed hackathons were developed, these included one on soil quality, another on the law and data, and a third on water quality, which was developed and managed by CEOBS.

The Addressing war-linked threats to water in Ukraine Challenge was held on the DigiEduHack platform in November 2024 — DigiEduHack is an EU initiative that aims to foster grassroots innovation, collaboration and creativity and to drive positive change in digital education. The Challenge aimed to encourage Ukrainian and European university students and staff to identify and develop digital solutions to address water quality issues in conflict-affected areas of Ukraine. The goal was to integrate citizen science as a participatory and digitally-driven approach to community empowerment. Along the way we hoped to build the knowledge of participants in both citizen science, and in the use of sensors and remote sensing methods.

The process began with an introductory webinar exploring how the war is influencing water quality in Ukraine and how water needs and threats may change over time, both in respect to Ukraine’s recovery but also as a result of climate change and Ukraine’s commitments on regulatory alignment with the EU.

It was the CEOBS team’s first hackathon and a learning experience for us too. We engaged contacts such as the Baltic University Network to recruit participants across the EU, and thought long and hard about the most appropriate format. We needed to ensure that its online structure was appropriate for Ukrainian participants living under power cuts and air raids. Instead of the normal format of 24-hours’ work or two intensive 12-hour days, we opted for a hybrid event combining elements of both a citizen science school, and a solution workshop.

Participants comprised 33 students in seven teams. Three were from Ukraine, with teams from Kyiv’s National Technical University of Ukraine, Lviv’s Ivan Franko National University, and Odesa Mechnykov National University. Three teams participated from Poland’s Rzeszow University of Technology, with the seventh mixed team comprising students and PhD researchers from Finland’s Aalto University and Paris Nanterre University. All teams completed the challenge and presented brilliant ideas on day two. They were supported by three mentors who helped the participants with the project design and the scientific basis for their ideas: Iryna Babanina, CEOBS; Dr Juliane Schillinger, Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre; and Dr Maksym Soroka of Ukraine’s Dovkola Network of citizen science. Alongside their technical basis teams also had to consider how their ideas would support civic participation in environmental decision-making.

On day one, participants learned how conflicts threaten water and received an introduction to citizen science, including its key principles and ethics. Juliane meanwhile provided global insights on the humanitarian dimensions on water in conflicts based on her work with the Red Cross. Alongside the theory, participants also learned about water sampling and selecting the most appropriate laboratories. Given the context, we also emphasised the importance of Explosive Ordnance Risk Education for citizen scientists; mines and explosive ordnance can be present in riverside areas and wetlands affected by fighting and can be a low priority for demining.

So, what solutions did the teams come up with?

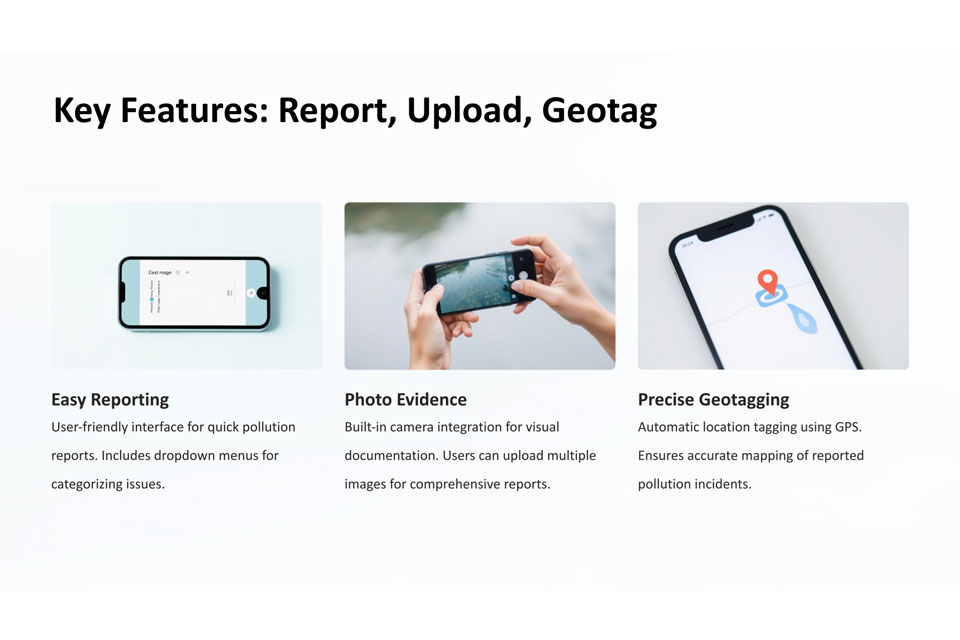

The United Ducks team suggested making environmentally friendly “ducks” that can purify water, help repair flora and fauna and that are equipped with sensors that can gather water quality data and send it to an app. The Powal and HydroSolutions teams from Rzeszow University of Technology presented mobile apps that would allow local people to report water quality issues, upload photos, share the location of contaminated water sources and alert citizens based on geographical proximity. An AI model would collate the data from multiple sources.

Publicly accessible water quality monitoring platforms already operate in Ukraine, such as the State Water Agency’s data geoportal, and EcoZagroza’s water data layer. The EcoZagroza system also allows citizens to report environmental issues or wartime damage to the State Environmental Inspectorate. Nevertheless, no simple real-time app dedicated to water quality currently exists.

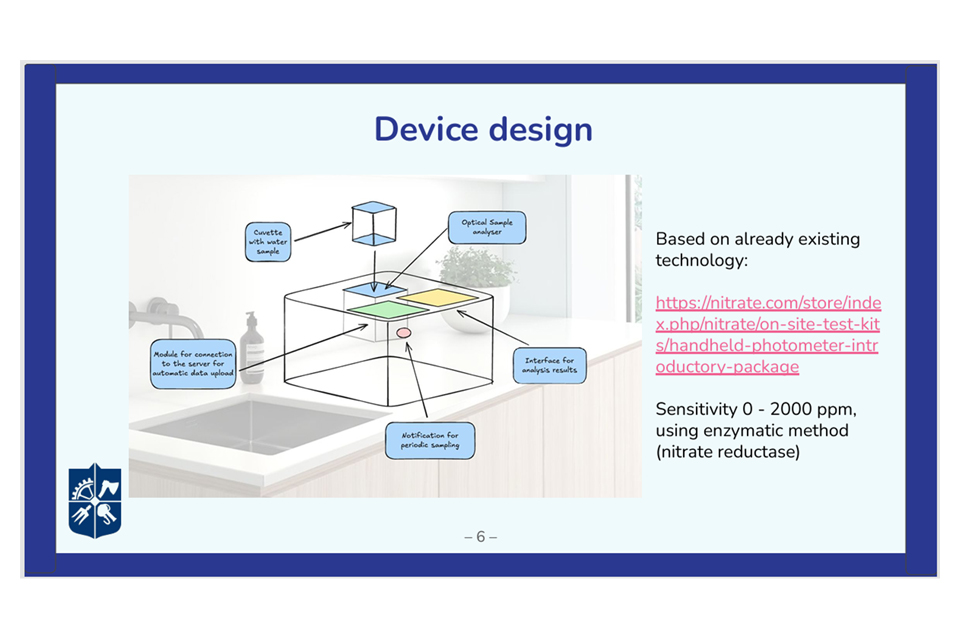

The AquaAlert team from the National Technical University of Ukraine conceptualised a rapid autonomous water quality monitoring system. Power cuts frequently disrupt water supply and wastewater treatment, contributing to nitrate contamination. The team proposed the use of an existing low-cost enzymatic nitrate sensor, and to set up a data collection platform offering transparent, real-time safety data and trend tracking. Local volunteers would be trained to operate the system, which could later be expanded to include phosphates and other pollutants.

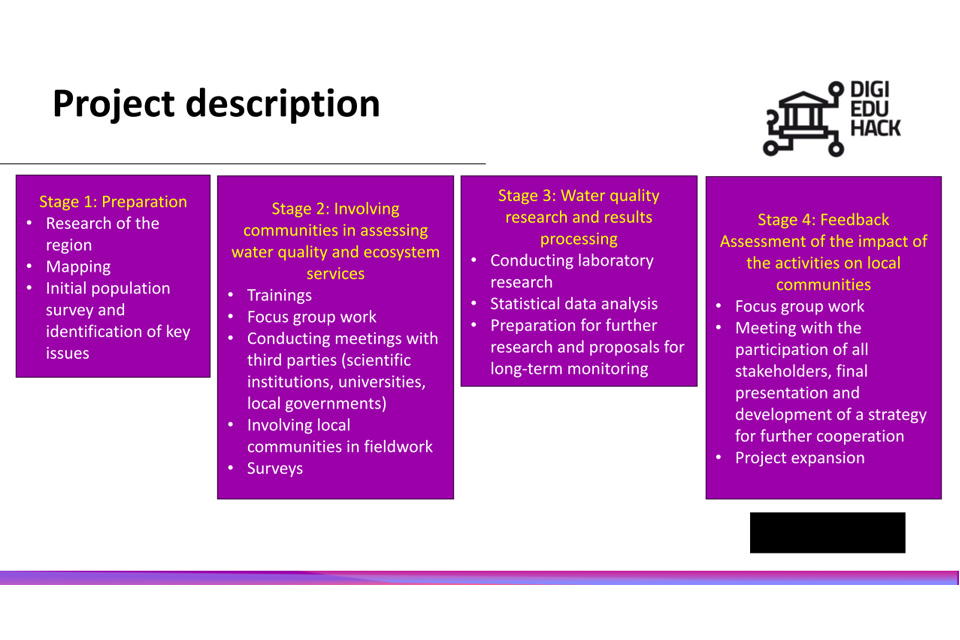

Lviv National University’s AquaVitae team addressed the aftermath of the destruction of the Irpin Dam for local communities. Flooding the Irpin river valley slowed Russian troops’ advance on Kyiv in the first days of the full-scale invasion. However, three years on, residents of Demydiv, Kozarovychi and other villages suffer from continued flooding and waterlogging, while water wells — the only local supply — remain unusable. The team emphasised the idea of community-driven field work to organise water quality monitoring.

WaterWatch, the team from Aalto and Paris Nanterre universities, focused on water quality issues linked to blackouts in Kharkiv. The industrial city’s energy facilities have been heavily damaged by Russian missile attacks. The team designed a water safety testing system using low-cost sensors, with the data shared in a Telegram chatbot that also provides users with instructions on what to do if the water is unsafe. The project had a well-thought-out design and was adapted to the needs of affected communities.

The OdesaEco team from Odesa State University focused on eutrophication along the Odesa coastline, where nutrient overload has degraded water quality, harming marine biodiversity and disrupting local ecosystems. For the first stage of a project, the participants showed how satellite data from NASA and Sentinel could monitor the eutrophication of the Black Sea and semi-enclosed bays near Odesa. The team suggested that the project could be scaled-up to include physical sampling when the security situation allows, helping to protect coastal water quality, support marine life, and improve the coastline’s appeal for tourism and fishing, thus benefiting the local economy.

The verdict on the project ideas

The teams’ ideas were judged by a panel of experts: Dr Mariia Pavlovska, a Researcher at the National Antarctic Scientific Centre of Ukraine; Dr. Nickolai Denisov, Deputy Director, Zoï Environment Network; and Eoin O’Donnell, Deputy WASH Cluster Coordinator in Ukraine. The panel assessed the projects based on their quality, relevance, originality, feasibility, sustainability and transferability, and provided detailed feedback to the participants. After a thorough review of each project presentation, the judges awarded the highest score to the WaterWatch team, with AquaVitae and OdesaEco in 2nd and 3rd, respectively.

As this was CEOBS’ first hackathon we were nervous ahead of the event but were ultimately blown away by the dedication and energy of the volunteer teams. Stepping back from the projects themselves, the event provided valuable and inspiring insights into opportunities for citizen science in Ukraine, both for assessing damaged water resources and for their restoration. That the teams could identify potential citizen science solutions for the Ukrainian context fits with wider global trends that have seen diverse water quality applications developed for citizen science.

Whether with blackout-resilient low-cost sensors or remote sensing, participants identified local and contextually relevant solutions. Many of these are not currently addressed by governmental bodies but could offer tangible solutions to the war’s impact on water quality, should they be picked up and implemented.

Iryna Babanina, Dr Anna McKean and Jay Lindle are all part of CEOBS’ Ukraine team. Huge thanks to all the participants for their energy and creativity, and to the mentors and judges for helping make the hackathon the success it was.